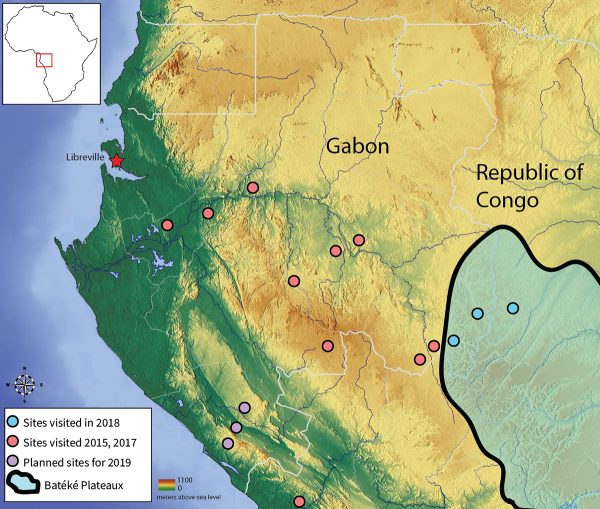

University of Florida Ph.D. student Gregory Jongsma has been obsessed with Africa’s wildlife since his childhood. Not the animals you might see on a safari, though. Each summer, Jongsma travels to Gabon, a country on the west coast of Africa, to study its vast array of frogs with the help of his local collaborators.

“The landscapes are beautiful. The people are amazing. I feel like I have the best job in the world,” said Jongsma, who works in the Blackburn Lab at the Florida Museum of Natural History. “When I was younger, I wanted to be a professional frog-catcher, but I didn’t know it was actually a job you could get.”

But fieldwork in one of the most understudied and remote regions of the world has its challenges, both logistical and scientific. In addition to navigating washed-out roads, dodging elephants and once finding a flesh-eating worm lodged in his foot, Jongsma is using genetics to explore how Central Africa’s environmental history over the last 2 million years has shaped patterns of frog species present there today.

Jongsma’s work focuses on identifying refugia, ecosystems that have been stable since the last glacial period when ice covered much of Earth’s surface. Refugia are often compared to “islands” in which certain species are isolated. Jongsma uses comparative biology, studying several species that live in the same areas, to assess how the frogs of these “islands” have changed over time.

“Biogeography is the study of the origins of plant and animal distributions, meaning that sampling must be done across the landscape being studied,” Jongsma said. “There had been so little work done in this part of the world that I didn’t know ahead of time what species I would find. I would go out, start collecting and it would come out in the wash what species we had enough of to do a proper analysis.”

Jongsma’s biggest thrill in the field is finding his target species in a new location. Often, frogs are specially adapted to their environments and can be susceptible to rapid changes in climate and habitat destruction. Uncovering the processes that generated the area’s biodiversity is a powerful conservation tool for learning how to protect Central Africa’s diverse frog populations, Jongsma said.

One of the more unusual species Jongsma has found is Trichobatrachus robustus, known as the “hairy frog” for the male’s outgrowths of skin filaments that look like wiry hair. It’s also known as the “Wolverine frog” for the bones that break through its fingers as a defense mechanism when the frog feels threatened.

“They actually scratch you. It’s like a cat scratch,” Jongsma said. “Finding Trichobatrachus was a highlight.”

Florida Museum image by Gregory Jongsma

For Jongsma, exact itineraries are nonexistent when he’s in the field. Once he arrives in Libreville, the capital of Gabon, the first step is finalizing permits to collect specimens. During his first trip in 2015, a planned four-day stop in Libreville turned into four weeks when he learned that the permits he’d requested had not been processed. Stuck in one of the most expensive cities in Africa, Jongsma decided to use a hospitality and social travel app called Couchsurfing to find more affordable housing.

“The couple I stayed with was amazing,” he said. “They’re credited in all the acknowledgements of my papers from that expedition.”

His collaborators have also become good friends. He places an emphasis on connecting them with UF and with each other to continue sharing techniques and ideas.

“A large part of what keeps me going back is that the local people are so unbelievably welcoming and fun to be with,” Jongsma said.

Because much of his work straddles both the Republic of Congo and Gabon, Jongsma chose to connect his collaborators from both countries by traveling with his Gabonese team into Congo by car. They were detained by border guards for nearly eight hours.

“The border gets maybe a car a week. They were accusing me of being an American spy, which I thought was particularly funny because they were holding my Canadian passport,” Jongsma said.

Jongsma said he was finally permitted to cross and was able to introduce his Gabonese collaborators, Abraham Bamba-Kaya and Elie Tobi, to Ange Zassi-Boulou, his Congolese collaborator. The researchers spent 10 days together conducting the first amphibian and reptile survey for Central Africa’s largest savannah.

“They’re right next to each other but don’t know each other and yet they all study the same types of species,” Jongsma said. “It’s important to get a diversity of backgrounds in science.”

Connections like these have been invaluable to Jongsma, who has also been able to collaborate with Gabonese researchers in the U.S. He has trained Bamba-Kaya, who works at Gabon’s Institute of Agronomic and Forestry Research, in molecular techniques and species distribution modeling in the Blackburn Lab. Tobi trained with a Florida Museum digitization expert and is working with Jongsma to digitize specimens from the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute in Gabon.

The specimens will be part of the National Science Foundation-funded iDigBio project. Based at UF, the project aims to make museum collections digitally accessible to researchers and others worldwide.

“I’m using 21st-century technology to answer questions that were being asked in 1852. It’s exciting what the future will bring in terms of technological advances to answer these age-old questions,” Jongsma said.

At the end of each trip, Jongsma leaves a selection of frog specimens with a museum in the coastal town of Gamba and brings any tissues he collects back to Florida. He uses museum specimens and tissues to better understand the genetic changes certain frog species have undergone over time. These changes also reflect shifts in Gabon’s landscape and can reveal the locations of previously unknown refugia, as well as the history of the area since the last glacial period.

“For me, a museum is like the closest thing to a time-travel machine. If I want to go back and look at a frog that was collected 150 years ago, learn something about its diet and diseases it may have been infected with, and potentially collect genetic information from it, that’s all possible,” Jongsma said. “If a collector hadn’t collected it and deposited it in a museum, it wouldn’t be doable.”

An important part of Jongsma’s work is “paying it forward” to future scientists by collecting specimens and adding them to the Florida Museum’s herpetology collection. In fact, he’s already planning his next trip to Gabon.

“Every time I go into the field, I come up with the idea for the next trip, and it’s when that idea hits me that it’s extremely exciting,” he said. “So far, Gabon has not failed me in terms of inspiring the next trip.”

Source: Gregory Jongsma, gjongsma@ufl.edu, 352-870-1634

Learn more about herpetology at the Florida Museum.

Learn more about Jongsma’s work.