Photo by Juan Francisco Ornelas

In stark contrast to southern Mexico’s surrounding dry plains, the mountains in Mesoamerica ascend into a secret world, enshrouded in fog. The mesmerizing flora and fauna create a mystical aura and the sounds of birds and Howler monkeys fill the air – picture a scene from “Avatar,” where mysterious creatures are a reality.

Mesoamerican cloud forests are home to some of the most diverse plants and animals in the world. Like sponges, they store water from the clouds and release it slowly, a vital process for replenishing and sustaining water. Palpable moisture and mild temperatures on mountain slopes where they occur support numerous native, endangered communities scientists have only begun to explore.

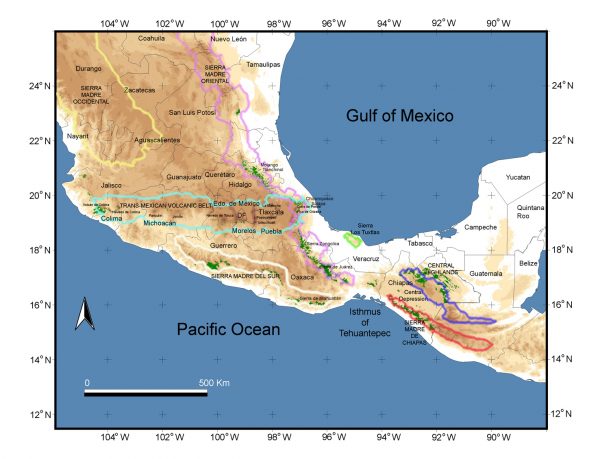

These biodiversity hotspots historically provided billions of gallons of fresh water, and yet the delicate ecosystems have been devastated for grazing, development, and coffee and coca farming. In northern Mesoamerica, which includes southern Mexico and Guatemala, 50 percent of the original cloud forest habitat has been destroyed and it occupies less than 1 percent of the total geographic area today. Cloud forests are naturally fragmented and among the most threatened habitats in the region.

Photo by Juan Francisco Ornelas

Hoping to create effective conservation plans for these important ecosystems, an international team of researchers analyzed genetic information of cloud forest plant and animal species to better understand the habitat’s evolutionary history. Using DNA markers and computer programs designed to reconstruct the past, scientists determined that while populations of diverse plants and animals endemic to the forests have similar geographic distributions today, they show genetic diversity among their populations – different cloud forest organisms from northern Mesoamerica may have complex different genetic histories. The research was published in PLOS One Feb. 7.

“A species will occur in different areas, but each area has its own genetic fingerprint, just as humans that are from Africa, or Asia or North America would’ve had their own genetic history because of the long period of separation before lots of human migration and intermingling,” said study co-author Doug Soltis, a distinguished professor at the Florida Museum of Natural History and the University of Florida biology department. “Populations of the same species may look very similar, but genetically, they’re different.”

Scientists have historically thought of cloud forests as a single habitat unit in northern Mesoamerica. These differences among populations reflect periods of isolation and different histories of migration over the past several million years during environmental changes, such as glaciations.

“What this information means from a conservation standpoint is that you can’t pick one cloud forest area and say, ‘I’m just going to preserve what’s here in this one spot,’ ” Doug Soltis said. “To preserve genetic diversity, you really need to conserve areas that represent different belts, or regions of cloud forest.”

Figure courtesy of PLOS one

In collaboration with colleagues from Mexico, Doug Soltis and Pam Soltis, also a distinguished professor at the Florida Museum of Natural History on the UF campus, conducted DNA analysis on five plant species: two trees, a shrub, a herbaceous plant and one epiphyte, a plant that grows upon another plant instead of in the soil.

“Geographic breaks in different species at the same places may look like they were all caused by similar environmental factors, but when you add the time component, you can see that they actually occurred at different times,“ Pam Soltis said. “That’s one of the things I think is most fascinating about the results of the study.”

Into the jungle

In 2011, study co-authors traveled to Veracruz, Mexico, to conduct phylogenetic analyses on the species in surrounding cloud forests. Researchers used comparative phylogeography, a field of genetics in which scientists collect sample populations and use genetic markers to reconstruct the past. “This is like CSI, but in natural populations,” Doug Soltis said.

Scientists analyzed DNA data for 15 different plant and animal species. In addition to the five plant species, they included three rodents and seven birds, three of which are hummingbird species. Eight of the species originated in North America, five in South America and two in Central America. The group represents the great diversity of organisms found in the highlands of northern Mesoamerica, which are recognized as one of Conservation International’s ‘Biodiversity Hotspots.’

“Even though we think of most of Mexico as having very dry-adapted organisms, in the cloud forests, you have a lot of very temperate or wet-adapted plants and animals,” Doug Soltis said. “A great example is the tree sweetgum, which we have growing here on the UF campus – it’s down in those cloud forests in southern Mexico even though it’s primarily a temperate plant from the eastern U.S. Beech trees are also there and you think of those as being in the northern United States, maybe in northern North Carolina or Virginia. The trees are growing there with tropical plants such as bromeliads and many ferns hanging from their branches. It’s a very striking place.”

Photos by Clementina Gonzalez (bird) and Eduardo Ruiz Sanchez

People of the forest

One of the interesting aspects of cloud forest habitats in Mesoamerica is the way indigenous peoples have adapted to live in these areas. “It’s hard to go anywhere there and not find people,” Doug Soltis said. “There are little towns everywhere.” Many depend on the forests’ resources and land for farming in order to survive. Evidence of this adaptation is seen in how farmers use the shaded canopy of forests to grow coffee.

“In one sense, a reason why some of these forests remain is because of the organic coffee demand – rather than cutting down a whole forest and just planting nothing but coffee there, farmers go in and cut out the understory, the low-growing plants that occur there, and plant coffee underneath the canopy of the trees,” Doug Soltis said. “It’s a blessing on the one hand because the forests might be gone otherwise, but on the other hand, it would be nice to have larger areas where you just keep the entire forest community intact.”

Scientists hope this type of research will help prompt the Mexican government to support conservation of cloud forest habitats in national or regional parks, he said.

“We talk about cloud forests as if it’s only one biological unit, but the worst thing that could happen is that this view could be used to lump everything together and we only protect one of these remaining areas of cloud forest,” Doug Soltis said. “That would be a bad conservation strategy and the genetic data provide the underpinnings for a more helpful strategy in which multiple areas are preserved.”

“It is now a highly fragmented and damaged habitat that requires immediate protection before it is too late,” he said.

Study co-authors include Juan Francisco Ornelas, Victoria Sosa, Clementina González, Carla Gutiérrez-Rodríguez, Alejandro Espinosa de los Monteros and Eduardo Ruiz-Sanchez of Instituto de Ecología, AC, Xalapa, in Veracruz, Mexico; Juan M. Daza of Universidad de Antioquia in Colombia; Todd A. Castoe of the University of Colorado School of Medicine; and Charles Bell of the University of New Orleans.

- The study may be viewed at http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0056283

Learn more about the Laboratory of Molecular Systematics & Evolutionary Genetics at the Florida Museum.