Along a bend in the Apalachicola River, 50 miles west of Tallahassee, Florida’s largest slice of visible bedrock towers more than 100 feet above the surrounding banks. With a rich fossil record of plants, Alum Bluff offers a glimpse of Florida’s forests 13 to 16 million years ago, and paleobotanists have been studying the site for more than a century.

Now a new study provides an overview of the finds from the last two decades, including 36 kinds of leaves, 10 types of fruits and seeds, seven unidentified fossils and a newly discovered species of elm.

“A site like this is rare in Florida, and the flora and fauna here are relatively diverse,” said Terry Lott, Florida Museum of Natural History paleobotany lab manager and first author of the study. “For Florida, it’s one of the few places where you can actually find fossil leaves, fruit, pollen and flowers in exposed sediment.”

Many Alum Bluff specimens are megafossils, or plant fossils that can be seen with the naked eye. Researchers have also found microfossils, such as pollen and fungal spores – invisible without the help of a microscope – that can provide useful data for specimen identification. Lott said during the Miocene, Florida’s Panhandle had temperatures similar to what today’s North Central Floridians experience.

The bluff is one of only eight major Miocene Epoch sites in Eastern North America. Finding Miocene fossils in Florida is particularly challenging due to the state’s sandy sediments and flat landscape, which can make fossils difficult to unearth and soil layers hard to spot, Lott said. In many parts of the state, older rocks from the Eocene are exposed, revealing marine shells consistent with higher sea levels instead of plant fossils.

Unlike most other Florida fossil sites, the sediment at Alum Bluff is a mixture of sand and clay. Lott said the Alum Bluff region might have been a delta that accumulated sediment and plant remains over millions of years. Leaves, fruit and seeds likely fossilized as they were buried beneath the sediment, where limited oxygen slowed the decay process.

Now protected by the Nature Conservancy in Florida, this region of the Panhandle is also known for its varied biodiversity. Thriving temperate plants make it one of five biological hotspots in North America, according to the Nature Conservancy.

Florida Museum photo by Kristen Grace

Today, as the landscape erodes and the Apalachicola River’s water level shifts with storms, fossilized blocks of sediment and plant remains tumble out from the soil layers, Lott said, making the bluff a perfect place for Florida paleobotanists to hunt fossils.

For delicate plant remains, dense sediments, minimal transport and lack of oxygen are the most important factors in plant fossilization and can act as nature’s preservatives, Lott said. But it’s still common for fossil plant specimens to remain unidentified. Researchers often rely on other components, such as fruits, seeds and nearby vertebrate fossils in the same soil layer, to gather as much information as possible.

“It’s really hard to identify something with just one leaf. Often, you’re just hoping that you might find more of the same leaf with more visible characteristics,” Lott said. “For instance, if you find a fruit from the same plant in the future, it could keep you from misidentifying species with similar leaves.”

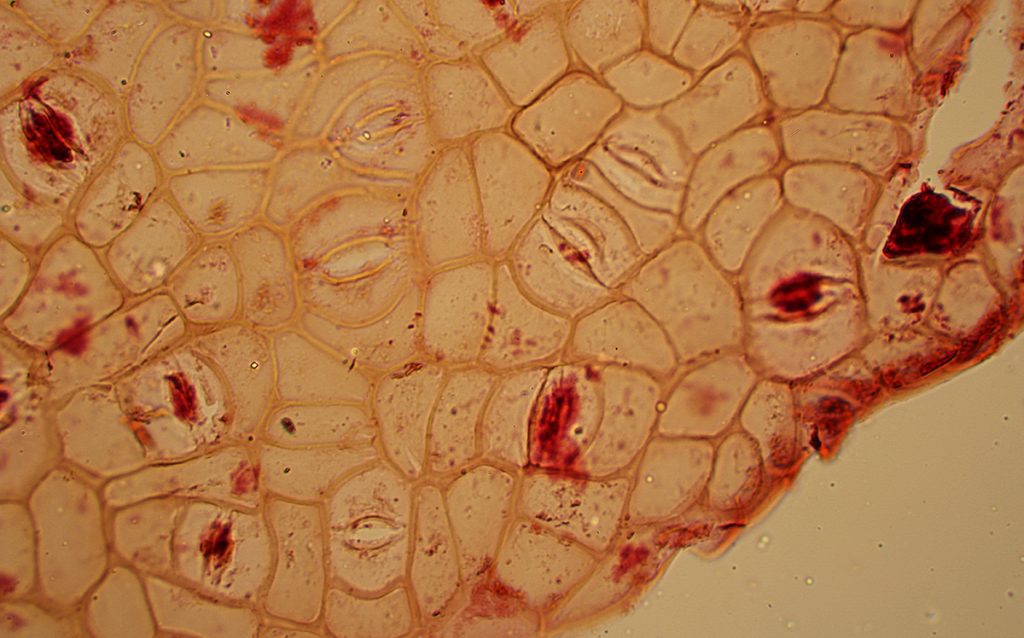

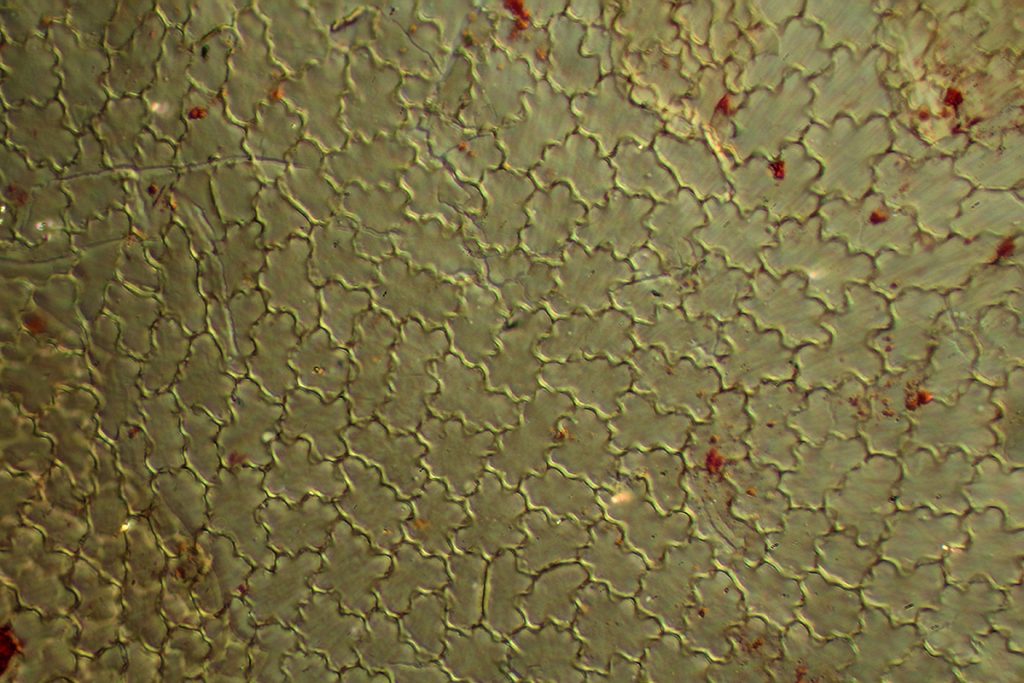

Often, paleobotanists rely on pollen, spores and the outer protective coating on leaves – called cuticle – to make identifications with certainty based on cellular patterns. Cells can range in shape from square to round to jagged, similar to interconnected puzzle pieces. This outer layer can preserve as sediment hardens and is exposed when a block of sediment is broken apart. This is called a compression, which may also include fruit and seeds.

“If you find a nut or seed that could be in the same family, maybe you can know which genus and if you’re lucky with cuticle maybe you get down to the species,” he said, adding, however, that sometimes the cell structures decompose, leaving behind what he calls “junk” – cells without a distinguishable shape.

Using this data to understand a region’s plant life can give researchers insights into its climate, precipitation and even ancient vertebrate life, often helping complete the picture for paleontologists and naturalists.

Florida Museum photo by Kristen Grace

At Alum Bluff, researchers have found mainly plant impressions, or fossilized outlines of ancient plants without any plant matter in them. Many of the plants that lived at the bluff in the Miocene would have shared similarities with modern hickories and elms, or Florida’s state tree, the sabal palmetto, Lott said.

“I’ve always wanted to know what things looked like 15 million years ago. To be able to have things preserved, even if there’s not much there, is still something,” Lott said. “You have a fingerprint of the past. The challenge is to try to identify it.”

The Florida Museum’s Steven Manchester and Sarah Corbett co-authored the study, which was published in Acta Palaeobotanica.

The Becker-Dilcher Paleobotany Fund of the University of Florida Foundation and the Graig D. Shaak Staff Enrichment Program of the Florida Museum of Natural History funded the research.

Source: Terry Lott, lott@flmnh.ufl.edu, 352-273-1933