Our lab explores the intrinsic and extrinsic processes that generate and maintain species diversity and phenotypic disparity. We focus primarily on small mammals in the montane tropical regions of Asia, Florida’s diverse sub-tropical landscapes, and Alaska’s boreal forest, but our research often spans broader geographical and phylogenetic scales.

We investigate morphological evolution and evolutionary ecology across mammalian taxa, from skeletal adaptations in climbing species to dietary macroevolution to phenotypic disparity within island communities. Our questions extend beyond any specific clade or taxonomic level, integrating foundational theories in evolutionary ecology with modern comparative methods and statistical tools.

Museum collections are central to our research. We use external measurements, locality data, μCT scans, DNA from tissues, and hair samples for stable isotopic analysis. We have an active collecting program in Florida and work with several labs in Southeast Asia to inventory the astounding diversity in this beautiful yet threatened part of our planet.

Below are a few active research topics:

Small Mammal Arboreality & Morphological Adaptation –

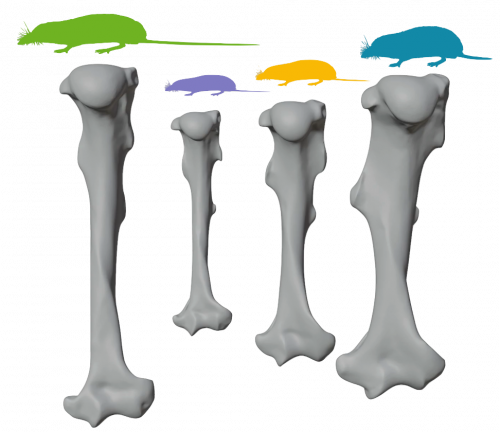

Arboreal species represent a functional guild that has evolved repeatedly across mammal clades. Climbing is also hypothesized to be linked to the origins of several major groups, including primates and the entire therian mammal radiation. Because climbing introduces unique physical constraints, convergent traits in distantly related arboreal species can signify climbing adaptations and help predict the locomotion of rarely observed or extinct species.

Our work has used skeletal proportions and shape to test for morphological signals of climbing in one diverse rodent clade (Murinae) as well as across all mammals, developing predictive models to illuminate locomotion in poorly studied and extinct species. We’ve also investigated how integrated morphological changes related to climbing contributed to the evolutionary success of murine rodents.

See related publications: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

Ecogeographic rules –

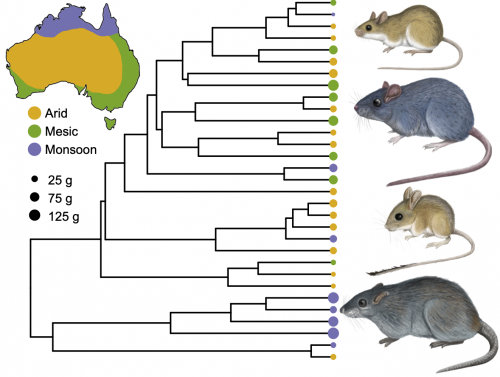

Ecogeographic rules describe correlations between organismal phenotypes and provide prima facie evidence of adaptation. With collaborators, I’ve worked on Bergmann’s rule (larger species in cooler climates) and Gloger’s rule (darker coloration in warm, humid climates). In Australia’s endemic murine rodents, we found that body mass is predictably larger in cool mesic environments, supporting Bergmann’s rule, and that body size tracked climatic changes throughout the Pleistocene (Roycroft, Nations, & Rowe 2020). In Furnariidae, the ovenbirds of Central and South America, we found a previously undescribed interaction between climate and light environment, where precipitation’s negative effect on brightness is strongest in cool temperatures, demonstrating the complexity of phenotypic adaptation (Marcondes, Nations, et al. 2021).

See related publications: 6, 7

Rethinking complex ecological traits such as diet –

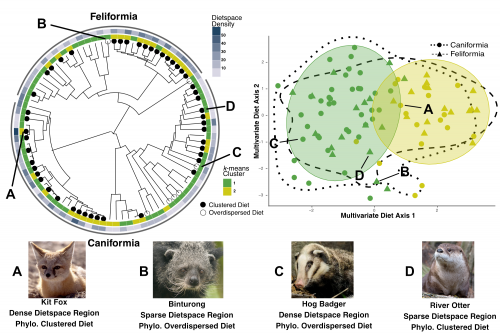

Despite recent advances in biological data quantification, complex ecological traits such as diet continue to be oversimplified into broad, discrete categories such as “carnivore” and “herbivore,” impeding understanding of these crucial axes of biological variation. Evolutionary ecologists need a path forward for collecting, quantifying, and deploying high-resolution, multivariate descriptions of ecological traits. Moreover, this categorization challenge extends beyond diet into virtually every corner of biology. With collaborators, we are working towards a new approach to diet quantification that uses ranked food importances to capture the multivariate nature of mammalian diet. From these rankings, a multivariate “dietspace” can be generated, allowing us to operationalize diet as any other multivariate trait space, like a morphospace.

See related publications: 8

Convergent evolution of functional traits in a “non-adaptive” radiation of Malay Archipelago shrews –

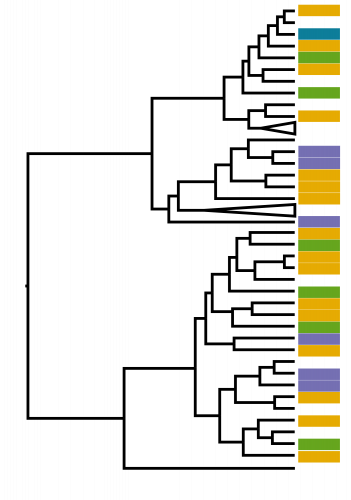

While many biological radiations are famous for their exceptional phenotypic diversity, some “non-adaptive” radiations, like Southeast Asian shrews, have rapidly diversified to form equally rich communities of remarkably similar-looking species. Interestingly, similar shrew morphotypes appear between different islands of the Malay Archipelago.

Using micro CT scans of museum collections, we’re testing for functional differences between species in communities and convergent evolution of these putative morphotypes between islands. Results will either support competition’s role in community assembly by highlighting functional differences in syntopic species, or suggest that function doesn’t play a substantial role in the formation and maintenance of these communities.

Using micro CT scans of museum collections, we’re testing for functional differences between species in communities and convergent evolution of these putative morphotypes between islands. Results will either support competition’s role in community assembly by highlighting functional differences in syntopic species, or suggest that function doesn’t play a substantial role in the formation and maintenance of these communities.

Elements of the vertebrate skeleton don’t always evolve in a coordinated fashion. This modularity has been widely demonstrated in mammalian and avian crania. While tests for integrated modules have been performed within the cranium and between limb elements, tests for covariance between cranial and limb modules are rare. Yet evidence of covarying skull and limb modules would be consistent with coevolution between feeding strategy and locomotion. We’re testing for cranial and postcranial modularity in Malay Archipelago shrews to answer: 1) How many modules are in the cranium and postcranial elements of small mammals? 2) How quickly do these modules evolve? and 3) How strong is the covariance between modules?

See Related Publications: 9