Globally, nearly all sawfish species are declining largely due to coastal habitat threats and over-fishing, but dwindling northern populations of smalltooth sawfish in the Atlantic may get a helping hand from Florida Museum researchers who plan to begin monitoring for the endangered elasmobranch in the Indian River Lagoon.

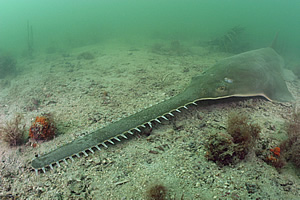

Photo by Doug Perrine, Sea Pics

About 100 million years ago, smalltooth sawfish emerged in the planet’s oceans, teeth splayed perpendicular from a long bill projecting from where their forehead should have been. Not much has changed in their evolutionary blueprint, though the continents have swung into new positions and different currents pump through the seas.

But today’s population of Pristis pectinata, an ancient member of the biological order Batoidea which also includes stingrays and skates, is dwindling and may have reached critically low levels. Smalltooth sawfish were once widely distributed along the shallow near-shore waters of the Gulf and Atlantic coasts, but today they are mostly restricted to the waters around Florida’s southern tip.

“Sawfishes as a group are among the most threatened of marine fishes,” said George Burgess, director for the Florida Program for Shark Research at the Florida Museum of Natural History. “Their decline is emblematic of the threat facing inhabitants of the world’s seas. As Americans and Floridians we have to do our part in conserving a species greatly at risk because of our own fishing and habitat-altering activities.”

Though their bodies look like that of a shark’s, sawfish are actually large, bottom-dwelling rays whose heads flatten into an elongated sawlike snout — called a “rostral saw” — spiked on each side with a single row of sharp, conical teeth. The saw’s tissue is dense with nerves that help it to locate food buried in the ocean floor where they use it to shuffle sediment and surprise their prey. When threatened, sawfish may sling their head side-to-side, brandishing their serrated projectile in a slicing motion. Using the same motion, they may slap schooling fish, stunning them. Smalltooth sawfishes rostrum’s are edged with 24 to 32 pairs of “teeth,” made from a calcified cartilage material. If damaged, their teeth will not regenerate.

Scientists estimate that the current North American population of about 2,000 is only 5 percent of their historic numbers. They are so uncommon that the species was listed under the Endangered Species Act in 2003. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature also categorizes the smalltooth sawfish as “critically endangered” under its Red List for Threatened Species. Other smalltooth sawfish populations exist off of South America’s Atlantic Coast as well as in the Pacific and Indian oceans.

Conserving Florida’s Atlantic Sawfish

Historic and scientific records combine to yield more than 300 instances of sawfish in the Indian River Lagoon on Florida’s Atlantic Coast since the pre-1900s, but their presence there today is not well understood and so Museum scientists plan to begin monitoring for smalltooth sawfish in the lagoon’s waters.

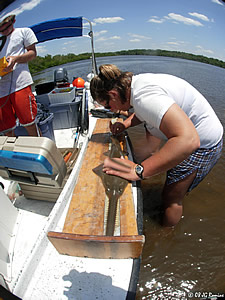

Photo by Jason Romine

“Historically, this was a very important place for sawfish, particularly for the adults,” said Burgess, who is planning the smalltooth sawfish-monitoring project. Previously, he also collaborated with other scientists in writing the sawfishes’ recovery plan, as well as in petitioning to list it under the Endangered Species Act. While sawfish are fairly well-studied on Florida’s southwest coast, scientists do not know as much about the populations living off Florida’s eastern coast.

“Monitoring sawfish catches will give us data on their distribution and abundance in the Indian River Lagoon, as well as their seasonality and how they use specific habitat,” Burgess said. “We lack this basic life history information for smalltooth sawfish, so we need to collect baseline data in order to know what areas need protection to ensure their recovery. Such studies will allow us to monitor the progress of the species’ recovery.”

In the future, Burgess plans to use an existing complex of underwater listening devices in the Indian River Lagoon to passively track sawfish that may be present. The fixed listening devices pick up unique “pings” given off by tags and store the information in a downloadable format. Researchers can also use a second method, called active tracking, where they work from a boat and use a hydrophone to track their study species in real time. It’s time intensive and can be only be done for 24 to 48 hours at a stretch, but it covers species activity out of range of the fixed listening devices. Both methods are typically used together. A third method involves satellite tags which transmit data in real time and are programmed to pop off after a certain length of time.

A Dwindling Species In U.S. Waters

Smalltooth sawfish are a slow-growing coastal-dwelling species that were once known to range from New York to Brazil. And while nearly 2,000 historic records of sawfish exist for Florida’s waters, there are only about 175 known records from all other states.

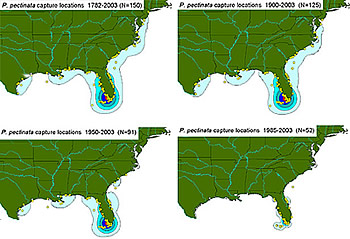

Photo by George Burgess

Burgess said sawfish likely declined rapidly in the United States, in large part because they prefer shallow waters near shore and because the people fishing these throughout the 20th Century primarily used gill nets, which were disastrously effective at snaring the sawfishes’ toothy bill.

“I assume that practically every sawfish ever caught here either was killed or at least had their saws removed because they damaged fishing nets or made great curios,” Burgess said.

Smalltooth sawfish grow to about 18 feet long, and live 25 to 30 years with most reaching maturity at about 10 years old. Each litter yields between 15 to 20 embryos. They are able to tolerate a wide range of salinities — a trait known to scientists as being “euryhaline” — including salt, brackish and fresh water.

In February 2008, a sports fisher in Tampa Bay caught a rare sawfish, though it was not immediately identifiable because its saw had been removed. And on July 18, 2002, a sawfish was caught off the coast of Savannah, Ga., – the first recorded north of Florida since 1963.

The Smalltooth Sawfish Recovery Team, tasked by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration with protecting and recovering the species in U.S. waters, identified parts of the Indian River Lagoon habitat critical to nursing sawfish populations back to healthy levels. On Florida’s Gulf Coast, Colin Simpendorfer, formerly of Mote Marine Laboratory, and Greg Poulakis of the Fish and Wildlife Research Institute, have studied sawfish from the Caloosahatchee River to the Keys. This stretch is considered the heart of where smalltooth sawfish spend their early years.

Encountering Sawfish Today

Recovery team members established an “encounters database” which helps them better understand how smalltooth sawfish use habitat, and therefore how human activities along the coast may impact their recovery.

Photo via Florida Memory, the State Archives of Florida

“Sawfish habitat lies within footsteps of every person living or recreating along Florida’s coast,” Burgess said. “Every person who puts a foot in the ocean or builds a dock or boathouse is operating in sawfish habitat.”

He said the database helps scientists understand how sawfish have used habitat over time, and how they use it today, which aids the recovery team in determining what habitat is most critical for sawfish survival and recovery. It also provides essential data needed for environmental permitting processes.

The National Sawfish Encounter Database, supported by National Marine Fisheries Service funding, is stitching together four existing but disconnected databases that have recorded human U.S. encounters with sawfish since 1782. While the majority of encounters are with commercial or recreational fishers who accidentally catch sawfish, other people also may have chance encounters.

But the project is not only computer based. As with many conservation issues, Burgess recognizes that people play a key role in the species’ fate. So he plans to use the database as a tool to meet with fishing groups and individuals along the coast and inform them of the fate of sawfishes, and what to do if they see or hook a fish.

“If hooked, a sawfish should be kept in the water at all times, any line or debris tangled around the ‘saw’ should be removed, and the fishing line cut as close to the hook as possible if the hook is not easily removable,” Burgess said. “It is better to leave the hook in than stress the sawfish by trying to remove a deeply embedded hook – the hook will rust away quite quickly.”

If an angler accidentally catches a sawfish, Burgess and his team ask that they record the date, location, depth and size of the sawfish and send this information, along with any photos or video, to the Florida Museum of Natural History, sawfish@flmnh.ufl.edu, where it will be incorporated into the National Sawfish Encounter Database.

- Learn more about the International Sawfish Encounter Database at the Florida Museum.

- Further reading: Sawfish Species Profiles

- Saw a sawfish? Report a Sawfish Encounter