Accessible only by boat, Cayo Costa comes alive when happy people step into the sunshine with their colorful bags laden with supplies for “a day at the beach.” The island is a paradise of natural wonders supported by modern conveniences and well-maintained hiking trails.

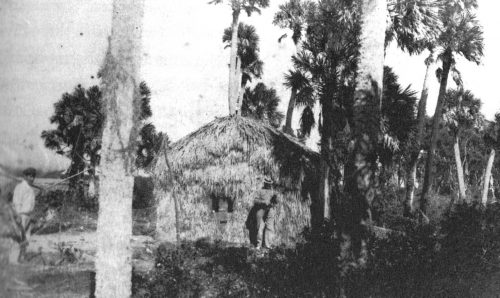

Today’s experience of Cayo Costa is far from the lifestyle of the early historic fishing families. They built palm-thatched huts without windows so they could keep mosquitoes out. They dug shallow wells for drinking and washing. Their boats had no motors, just sails and oars. Their fishing techniques were based on ancient traditions using stop nets, seine nets, dip nets, and gill nets just like their predecessors, the Calusa.

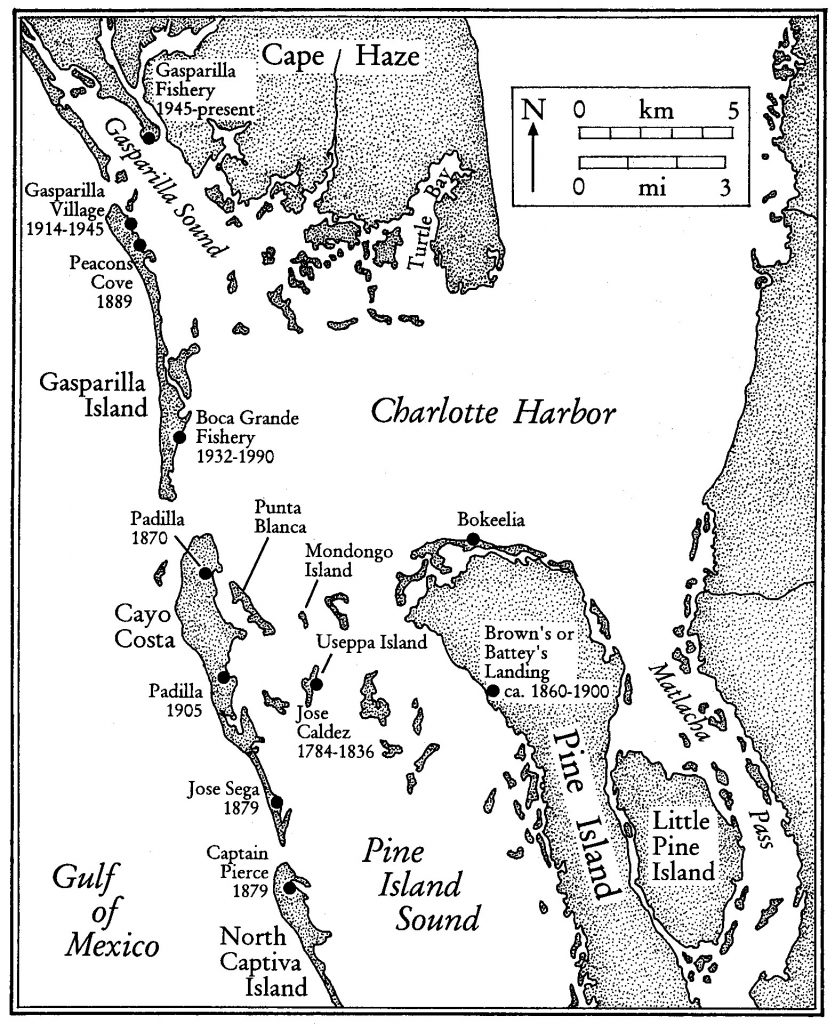

Today Cayo Costa has nine recorded “historic sites,” including the remnants of two fishing villages, a homestead, three U.S. military and maritime-related sites, and two cemeteries. In 1959, the federal government turned over its 640-acre reservation to Lee County for a park. In 1976, this parcel was incorporated into the 2416-acre Cayo Costa State Park.

The Quarantine Trail leads northward to the site of the U.S. Quarantine Station, first built on neighboring Gasparilla Island in the late 1800s and then moved to Cayo Costa in 1904. Consisting of a long dock with a roofed structure, and with outbuildings on the north shore, it remained there until destroyed by the hurricane of 1926. During the era of Yellow Fever, it served international ships loading phosphate at Boca Grande. Local pilots such as Captain Nelson and Captain Johnson guided each ship into port. Ships at anchor flew a yellow quarantine flag and waited for a doctor to examine everyone on board. Ships stayed several weeks. Dr. Perry McAdow occasionally converted the storeroom of the quarantine station into a dance floor for visiting dignitaries and ship’s officers. During epidemics, doctors not only treated the sick, they also arranged for burial of the dead in mass graves on Cayo Costa.

According to Charles Foster’s The Benevolent Dane, the pilot Captain Peter Nelson (1839-1919) was born in Denmark and arrived in Florida around 1865. He named the town of Alva using the Danish word for its beautiful white flowers. He set aside plots of land for the school, park, church, and library. He served on the earliest Board of Lee County Commissioners until he was seen drinking in public. He resigned and moved to Cayo Costa. There he served as a teacher, postmaster, ship’s pilot, and government employee.

Robert F. Edic in Fisherfolk of Charlotte Harbor, Florida recorded Esperanza Woodring, who in the early 1900s attended the one-room schoolhouse on Cayo Costa. “Well, the first teacher that I had was named Captain Peter Nelson. Now, I know you have heard of him. He was a great old guy, I will tell you.” Today, visitors to the Cemetery Trail see Nelson’s prominent headstone, etched with the words, “After life’s artful fever/ He sleeps well.”

Archaeologists have discovered that an estuary-based fishing culture thrived in this region almost six thousand years ago. The well-known Calusa, who lived in the area when Europeans first arrived, continued this ancient fishing tradition. These cultures caught all of the species mentioned by today’s fisherfolk, and prospered within these great fishing grounds for thousands of years.

During the Cuban Fishing Era (1687-1835), fishing ranchos existed on Cayo Costa. Cuban fishing captains hired Native Americans as fishing guides. At first the Cubans used only hook and line for grouper in deeper water. Then they adapted to the local net-fishing techniques. A very lucrative mullet fishery emerged. According to William Marquardt in The Archaeology of Useppa Island, by the late 1700s more than 30 Spanish vessels based in Cuba were sailing regularly to southwest Florida to fish and trade.

Many different races worked as deck hands on Cuban vessels. Pine Island Sound became a meeting ground for divergent cultures, all practicing traditional Calusa fishing methods. According to Edic, the eighteenth century workers were coastal Indian people, Spanish-mission Indians fleeing the British in northern Florida, escaping slaves from the American South, and various “mixed-blood natives living a nomadic existence.”

In 1814 Indian people from present-day Alabama fled into Spanish Florida after a major defeat by Andrew Jackson. These newly homeless people joined others whom the Spanish called cimmarónes, meaning “wild, untamed,” who by mispronunciation (the Indians had no “r” sound in their language) became known as Seminoles. During the 1800s war was declared upon the Seminoles three times, but they were never defeated.

In 1821 Florida became a territory of the United States. The 1830 Indian Removal Act forced Spanish Indians, Seminoles, and other Native Americans to immigrate to reservations west of the Mississippi. Noncitizen Cuban commercial fishermen were ordered to leave. Indian wives and children (some baptized in cathedrals in Cuba) were removed to reservations while their husbands and fathers returned to Cuba. One Cuban man protested that he lost three wives to the Indian Removal Act.

Resistance was heavy but the military prevailed in the environs of Pine Island Sound. A Naval Lieutenant wrote in 1836: “All the old Ranchos were visited, but they had been abandoned and for the most part destroyed during the last season.” By 1848, a military reservation on the northern end of Cayo Costa was concerned with the smuggling of liquor and arms to the Seminoles.

According to Marquardt, a map based on survey data of 1859 showed Cayo Costa’s north-central part with two large buildings and two small buildings known collectively as the “Burroughs Ranch.” During the Civil War (1861-1865), a Union blockade at the northern end of Cayo Costa sealed off Charlotte Harbor. The military reservation on Cayo Costa continued.

After the war, Hispanics returned and fishing ranchos were again established. A survey by the Smithsonian Institution in 1879 located the Padilla rancho on the northeast side of Cayo Costa facing Pelican Bay. The José Sega fishing rancho was situated along the southeast bay.

These early modern fisherfolk caught mullet, spotted sea trout, redfish, pinfish, pigfish, pompano, oysters, clams, and scallops. In some cases they netted so many fish their nets broke. Their fishnet repair kits resembled those found in Calusa artifact assemblages, including handmade wooden shuttles for pulling line through, and net mesh gauges of three sizes: small, medium, and large (the gauge is used as a measure for how far apart to tie the knots). The sizes of the net mesh gauges matched those of the Calusa to within millimeters.

The early Burroughs Ranch grew to twenty fishing families with a school established in 1887, a post office at the Quarantine Station in 1904, and a grocery store. During that era, several families, including the Padilla, Coleman, Spearing, Woodring, and Darna families, resided on Cayo Costa. According to the US Commission of Fish and Fisheries, in 1870 “the Captiva fish ranch…produced 660,000 pounds of salted mullet and 49,500 pounds of dried mullet roe. On south Cayo Costa, José Sega, the head ranchero along with 26 fishermen, yielded about a quarter of that amount. Ranchero Tariva Padilla (Captain ‘Pappy’) and his crew of 23 Spanish and one American produced about the same.”

The fishing family patriarch, Toribio “Tariva” Padilla (1832-1910) was born in the Canary Islands, immigrated to the Florida Keys, became a U.S. Citizen in 1862, and married Lainey (Juanita Parez), a Mexican woman, in 1867 in Key West. According to his great-granddaughter, Virginia Padilla Morton, his first name was spelled Toribio on his birth certificate, his marriage certificate, and citizenship papers.

The Padillas in 1901 were forcibly removed from the military reservation for allegedly trading Cuban goods such as tobacco and aguardiente (a distilled liquor). By 1905 they moved to a bay on the central east side of the island. Fisherfolk call it Tariva Bayou. Their great-grandson Richard Coleman explained to Edic, “He did not do the fishing himself. He was a boss. He would see that [the fish] were split and salted, and all of that…He would trade the fish in Cuba for liquor and would get a little money. He would bring that back over here.”

In the early to mid-1900s the fishing families attended school and delivered their fish to the ice house at Punta Blanca. This island, along with the 1922 “Fish Houses of Pine Island Sound,” will be discussed in the next part of this series.

This article was taken from the Friends of the Randell Research Center Newsletter Vol 12, No. 4. December 2013.