As readers of this newsletter know, the Calusa who lived on the southwest Florida coast were accomplished engineers and builders who had a rich social, political, and spiritual life.

But what if I were to ask you about their equally awe inspiring neighbors to the east, the Mayaimi or Belle Glade archaeological culture – the people who lived in the Kissimmee River Valley and around Lake Okeechobee? Some folks might respond, “Oh! The people that lived at Fort Center!” This is partly because the only widely publicized work on Belle Glade area archaeology is about Fort Center, but it is also because not much work has been focused on this part of Florida.

The Belle Glade culture lived in a vast, wet landscape. The Kissimmee-Okeechobee-Everglades watershed was once full of fl owing water for six to nine months of the year, with tree-island hammocks providing the only dry ground. However, during the dry season the water receded in many areas, leaving the landscape muddy and dotted with ponds. The Belle Glade people lived on the tree islands and depended for food on the plentiful fish (primarily catfish, gar, and bowfin) and turtles. They also hunted deer and other mammals, and used their strong mammalian bones to make tools. This was necessary due to a lack of local stone. They also imported marine shells and shark teeth for making tools, and made a pottery known to archaeologists as Belle Glade Plain.

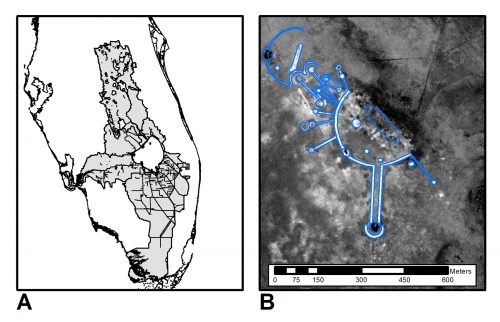

The most conspicuous part of the Belle Glade culture was the monumental architecture they built across the landscape. Over the course of nearly 2,000 years, these people built a variety of complex earthworks ranging from circular ditches to vast arrays of geometrically shaped sand ridges. The later forms are particular fascinating. Known as “Type B circular-linear earthworks,” each consists of a large semi-circular sand ridge that partially surrounds a midden-mound. From the semi-circle, multiple linear sand ridges radiate outwards like the spokes of a wheel or the rays of the sun, and the ridges end in large conical sand mounds.

Over the past few years I have been thinking about these earthworks in terms of the way Belle Glade peoples understood their world. Like other Native groups, they would have understood the importance of relationships, not only between people but also between different elements of their landscape and between important places on the landscape. I have been able to identify several of these important relationships, each of which is embodied in the architecture.

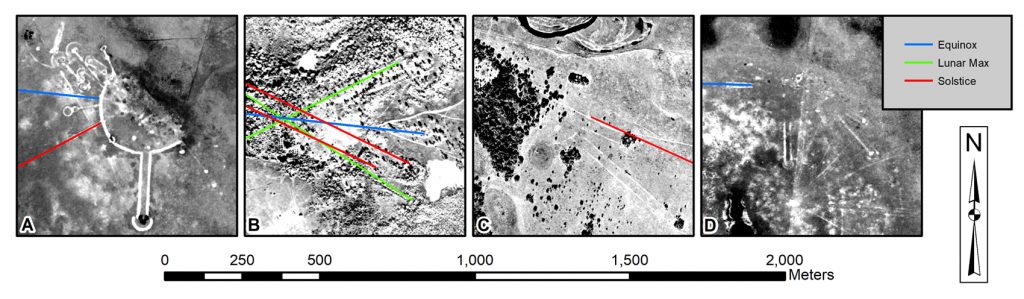

First, the relationships between the cosmos, landscape, and time are embodied in the linear ridges. Many of the linear ridges that radiate outwards are aligned with celestial events that are recurrent or cyclical, such as the solstices and equinoxes we see each year. Such alignments reveal a knowledge of the relationships among landscape, animal patterns, time, and the all-important water levels across the landscape. The spring equinox marks the onset of the rainy season, the summer solstice signals the peak of heavy rains, the fall equinox marks the end of the heaviest rains, and the winter solstice signals the beginning of a drying landscape. These differences in water levels are tied to animal distributions, behaviors, and breeding seasons. These are important to fisherhunter-gatherers, especially given the significance of relationships for Native Americans between people and non-human animals.

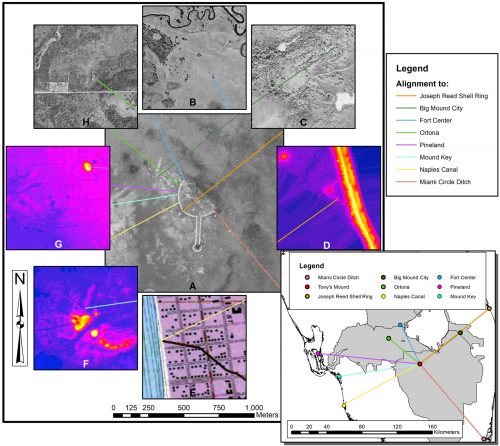

Second, the relationships between people and places on the landscape are also embodied in the linear ridges. If you extend the lines of these ridges across the entire landscape, they line up with monumental architecture at other important sites! Many of these alignments are to other Belle Glade earthworks in the Okeechobee Basin, but some are to important places where large numbers of people were buried in water, such as the charnel pond at Fort Center and the Lake Okeechobee burials at Ritta and Kreamer Islands. There are also examples of alignments to sites on the Atlantic and Gulf coasts.

Particularly intriguing are the alignments to Pineland and Mound Key, which we know to be two of the most important Calusa sites. Both of these sites have multiple alignments converging on them from several different Belle Glade sites. This suggests that these were very important places to the Belle Glade people, and further demonstrates the long-term relationships between coastal and interior peoples.

Archaeologically we know that a relationship began developing between them by at least AD 500. This is known through the presence of Belle Glade pottery at Calusa sites, which by AD 1000 had become the major pottery throughout the Calusa heartland. These alignments help to show that this association was important enough to the Belle Glade people to represent it in their architecture. To me, this suggests that it is a relationship we should explore further in archaeological studies because it will help give us a much richer understanding of the dynamics of the history of South Florida’s Native inhabitants.

For more details, see Lawres, Nathan R., 2017, Materializing Ontology in Monumental Form: Engaging the Ontological in the Okeechobee Basin, Florida, Journal of Anthropological Research, Volume 73, number 4, pp. 647-696. See this paper for sources of all maps and photos used in this article.

This article was taken from the Friends of the Randell Research Center Newsletter Vol 17, No. 1. March 2018.