Exciting archaeological discoveries often happen long after the excavation tools are put away. This is one reason why museum collections are so important.

A case in point: In 1990, volunteer excavators at Pineland’s Operation H unearthed a two-inch-long, odd-shaped bone from a large mammal. “Probably one of those funny ankle bones from a deer,” one might have said to the other. This would have been a reasonable guess, because bones of white-tailed deer are usually the only large-mammal bones found at Pineland. The odd bone was placed in a bag with many other bones — mostly from fish — and sent to the field lab. There, another volunteer cleaned the bones and yet another cataloged them. Later the bag made its way to Gainesville and settled in the basement of the Florida Museum of Natural History. Not chosen for immediate analysis, the bones were carefully stored for future research.

Some years later, a UF Anthropology student was assigned to search through the bag (and many others) to study the deer bones. When he compared the odd bone to those from a modern deer skeleton, there was no match. If it wasn’t deer, what was it? A comparison with all other possible candidate skeletons ensued. There were no matches, at least not at the Florida Museum.

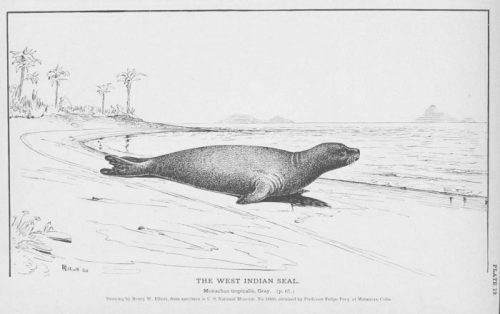

I suspected that we had a bone from a Caribbean Monk Seal, the one Florida mammal for which the museum has no representative skeleton. Sadly, this native, tropical seal became extinct in the mid twentieth century, and only a few individuals were ever collected for study. An internet search determined that the closest skeletons were in Washington D.C. at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History (NMNH). To confirm the identification, we would have to compare our bone with theirs. Meanwhile, more similarly odd-shaped bones surfaced in an old collection from Sanibel’s Wightman site.

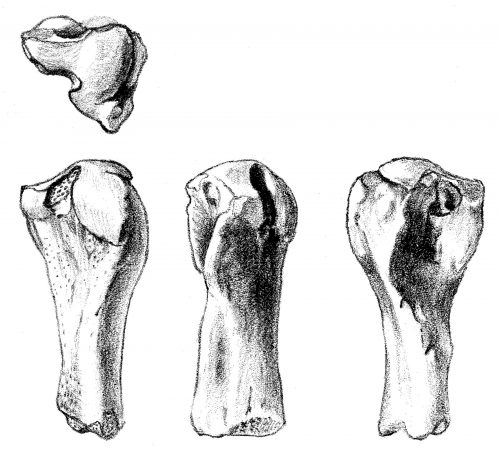

Finally, an opportunity for a trip to the Smithsonian presented itself. In September, 2004, collections manager Charley Potter guided Bill Marquardt and me through the NMNH’s skeletons as we worked to identify the Pineland and Wightman bones. We quickly saw that our Pineland bone was indeed from a Caribbean Monk Seal — specifically, it was the fourth metatarsal from a left hind lipper. Most of the Wightman bones were fragmented and more difficult to identify, but as luck would have it, Peter Adam, a University of California scientist proficient in monk seal osteology, was present that day. With his help, we identified about a dozen of the bones, all likely from one individual.

So, how and when did an isolated monk seal bone come to rest at Pineland? The bone lay between a late Caloosahatchee I period Indian midden (about 1,650 years old) and a layer of mangrove muck. Above the muck is a younger Caloosahatchee IIA period midden (about 1,450 years old). The muck layer occurs across much of the Pineland site at nearly the same elevation. In several excavations, the layer was underlain by a thin, intermittent layer of articulated sea shells, bones, and sea urchin parts — the remains of animals that are often carried in by a storm surge. These are about 1,650 years old, indicating that the storm may have impacted the people who lived there. Bones of at least one loggerhead sea turtle and one bottlenosed dolphin indicate that the surge was powerful enough to drown these animals—powerful enough also to drown a seal. Human survivors of this storm might have taken advantage of the seal (and other food resources that the surge left behind), butchering it and leaving behind the back flippers. This is only one possible scenario, and artist Merald Clark depicted it for an interpretive sign, now installed along the Calusa Heritage Trail at Pineland.

Perhaps one day volunteer excavators will find more of the seal skeleton. For now, at least we know that monk seals once swam the waters near Pineland some 1,650 years ago.

This article was taken from the Friends of the Randell Research Center Newsletter Vol 4, No. 1. March 2005.