A troubled economy and problems related to climate change are not newcomers to south Florida. Over 1,200 years ago, the once-rich estuarine fisheries of south- west Florida were greatly depleted and the region’s Native American inhabitants were forced to rely more heavily on shellfish and difficult-to-get Gulf of Mexico fish for food.

This dire situation would have spelled the end of many societies. Yet new research co-sponsored by the Randell Research Center indicates that the ancestors of the Calusa turned proverbial lemons into lemonade. Although they lacked the terrestrial resources that formed the basis of most New World civilizations, the Calusa had enormous numbers of discarded shells at their disposal. Innovative leaders encouraged the use of these shells to create a regionally organized wood- working industry. In doing so, they built an economic engine that helped drive Calusa society to unequalled heights.

My research began with a comprehensive study of the shell axes and adzes held by museums and research facilities in Florida. I measured and photographed 441 woodworking tools from 93 archaeological sites and submitted several dozen specimens for radiocarbon dating and chemical sourcing studies. The evidence is clear — the Charlotte Harbor/Pine Island Sound/ Estero Bay estuarine system was ground zero for a major shell-tool manufacturing industry that experienced a substantial reorganization 1,200 years ago. More than 80 percent of the unfinished shell tools, which provide direct evidence of tool- making, came from the region. Sourcing and tool shape studies indicate that the Calusa traded the tools they made with neighboring groups, particularly Lake Okeechobee people. Moreover, the new dates indicate that tool production more than doubled after A.D. 800. Significantly, nearly all of the unfinished tools from this later period are found in major Calusa political centers and a handful of small sites adjacent to the Gulf of Mexico.

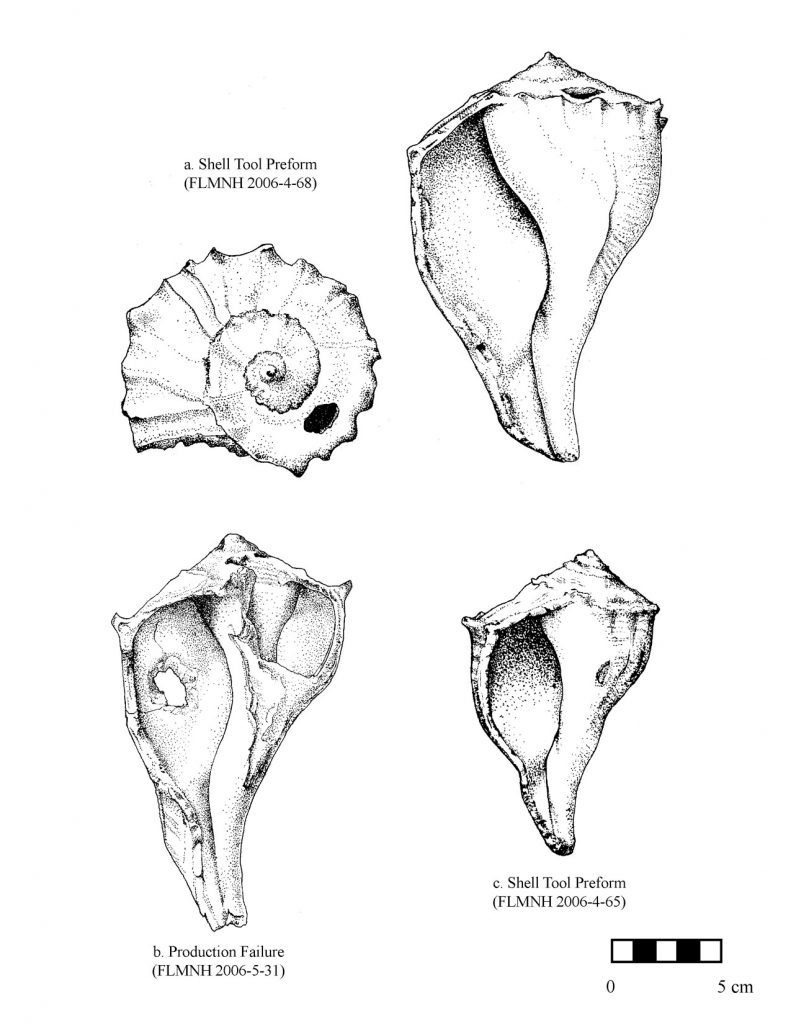

In order to help verify the museum study results, I conducted excavations at two of the smaller sites that had yielded large numbers of unfinished tools. With the help of over 50 Randell Research Center, UCLA, Florida Gulf Coast University, and Useppa Island Historical Society volunteers, the Useppa Island and Buck Key digs produced an unprecedented bounty of toolmaking evidence. These deposits contain the highest volumes of raw materials (lightning whelk shells), shell-working tools (shell hammers, shell pounders, and stone grinding implements), and shell-tool-making waste products ever documented for this technology. Detailed studies of the manufacturing byproducts indicate that these deposits represent well-organized shell tool workshops where skilled craft specialists produced large numbers of standardized woodworking tools. Radiocarbon dates place these workshops at the heart of a post-A.D. 800 region-wide economic boom.

The available evidence suggests that ambitious leaders in the Pine Island Sound region harnessed emerging shell working and wood working industries in order to increase their wealth and power after A.D. 800. By encouraging shell workers to make large numbers of axes and adzes that could be used by wood workers to create fleets of canoes, monumental buildings, powerful religious and political symbols, and breathtaking artwork, these leaders transformed a small-scale, locally oriented, and more egalitarian society to that of a larger, outward-looking society, with a strong, centralized government. With a firm economic foundation, the Calusa went on to become the powerful political force that is recorded so vividly in the pages of Florida’s history books.

This work was made possible by funding from the National Science Foundation, the UCLA Department of Anthropology, the UCLA Friends of Archaeology, Garfield Beckstead, and Alvin Flury. Research support came from the Florida Museum of Natural History, Historical Museum of South Florida, Florida Bureau of Archaeological Research, the National Park Service Southeastern Archeological Center, J. N. “Ding” Darling National Wildlife Refuge, Useppa Island Club, Barbara Sumwalt Museum, Randell Research Center, UCLA Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, NSF Arizona Accelerator Mass Spectrometry Laboratory, and UCLA Molecular Instrumentation Center. My thanks to one and all.

This article was taken from the Friends of the Randell Research Center Newsletter Vol 7, No. 4. December 2008.