Florida Museum of Natural History researchers have co-authored the first comprehensive study on the evolution of two agricultural pests commonly used as model organisms.

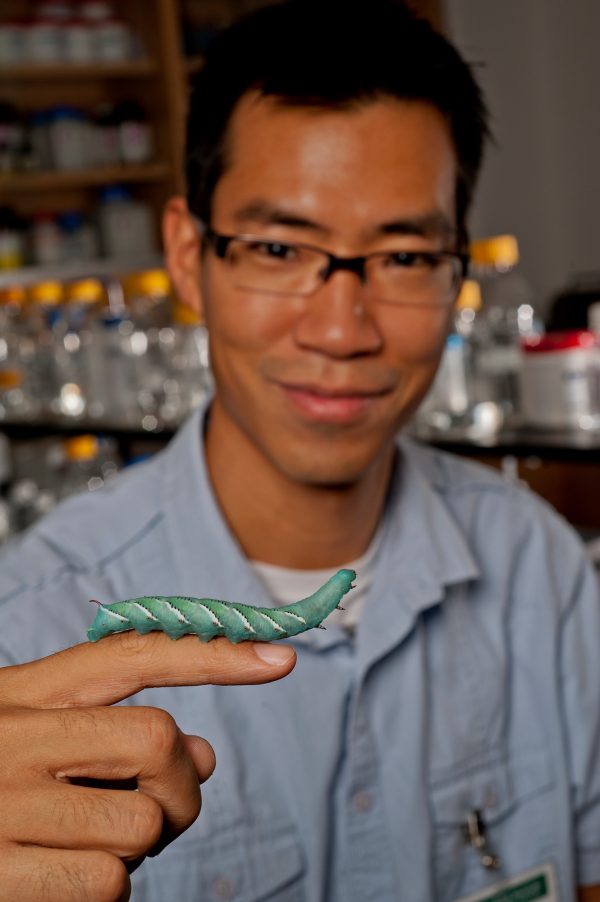

Florida Museum photo by Kristen Grace

Tobacco and tomato hornworms are among the largest caterpillars, able to individually devastate an entire plant if left unchecked. Despite their use in many fields of biology, the relationships of these hawkmoths have been confused for more than 50 years. The study published online May 3 and scheduled for the September 2013 print edition of Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution shows they are not as closely related as previously believed, providing a new baseline for determining correct classifications within the group, said lead author Akito Kawahara, assistant curator of Lepidoptera at the Florida Museum of Natural History on the University of Florida campus.

“When people make decisions about these species, they can’t assume that they are most closely related – there are other species in between that we didn’t know belonged there,” Kawahara said.

The tobacco hornworm, Manduca sexta, and the tomato hornworm,Manduca quinquemaculatus, are widespread hawkmoths occurring as far north as New York and west to Hawaii. Their common use as model organisms is a result of their large size, short life cycle and simple nervous system. Researchers conducted geographical and DNA analysis of 51 wild Manduca species, representing about 73 percent of species in the genus to determine Manduca originated in Central America, contrary to previous assumptions the genus was from South America.

“They originated in Central America, then radiated to North and South America,” Kawahara said. “It was kind of surprising because there are many species in South America.”

More than 1,000 hawkmoth species occur worldwide, distinguished as some of the fastest and most proficient flying insects. Their long proboscis, or mouthpart, makes them important pollinators, since many flowering plants may only be pollinated by hawkmoths. Species in the genus Manduca are often confused due to similar wing patterns, Kawahara said.

“There’s still a lot of confusion about this genus, despite being a major model group,” Kawahara said. “From this study we found there are other genera mixed in with Manduca, so we may need to formally change some scientific names.”

The genus name Manduca means glutton in Latin, since tobacco and tomato hornworms can defoliate the crops. They are mainly a problem in small gardens, since many large farming operations control them with pesticides, Kawahara said.

The team plans to continue researching the evolution of Manduca and aims to focus future efforts on genetic changes within the model species, rather than between species in the genus, Kawahara said.

“What we’d really like to do is look at the evolution within Manduca sexta,” Kawahara said. “We want to see how populations have changed over time and the amount of genetic differences within. A lot of people, when they study Manduca, don’t really know where their study animals actually came from or how genetically different they are from the things that are in the wild.”

The research was funded by grants from the National Science Foundation and National Geographic Society. Study co-authors include Jesse Breinholt, Francesca Ponce and Lei Xiao of the Florida Museum, Jean Haxaire of the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle de Paris, Greg Lamarre of Université Antilles Guyane, Daniel Rubinoff of the University of Hawaii and Ian Kitching of the Natural History Museum, London.