This is my fifth trip to Panama for paleontological field work. Since I started working with the project a little over a year ago, we have been collecting fossils along the shore of Lago Alajuela in Chagres National Park with more and more emphasis. One reason for this focus is that as the expansion of the Canal nears completion, it is important to identify other outcrops where we can collect important fossils. The Alajuela Formation is an exciting place to work because we find fossils of terrestrial vertebrates (exploration of the area started with the discovery of a gomphothere tooth), marine invertebrates, shark teeth, and fossil wood.

The fossils from the Alajuela Formation date to the mid-late Miocene and they tell us about the distribution of plants and animals leading up to the Great American Biotic Interchange. The Miocene lasted from 23 Million years ago to 5 Million years ago, but the Isthmus of Panama was fully formed only ~3.5 Million years ago, allowing animals to walk between the continents for the first time. Druing all of the Miocene, the Central American Seaway was a major barrier and only a few species managed to cross.

One of my roles in the project so far has been to document the diversity of plants in the Alajuela Formation that are known from the fossil woods. So far we have close to 100 specimens, and at least 30 different wood types (species). This is very diverse for a fossil wood assemblage, but probably what we should expect from a Neotropical forest. Several interns, including Chris Nelson, Carolyn Thornton, and Jeremy Dunham have played a role in understanding the Alajuela woods so far, and these three are on this trip.

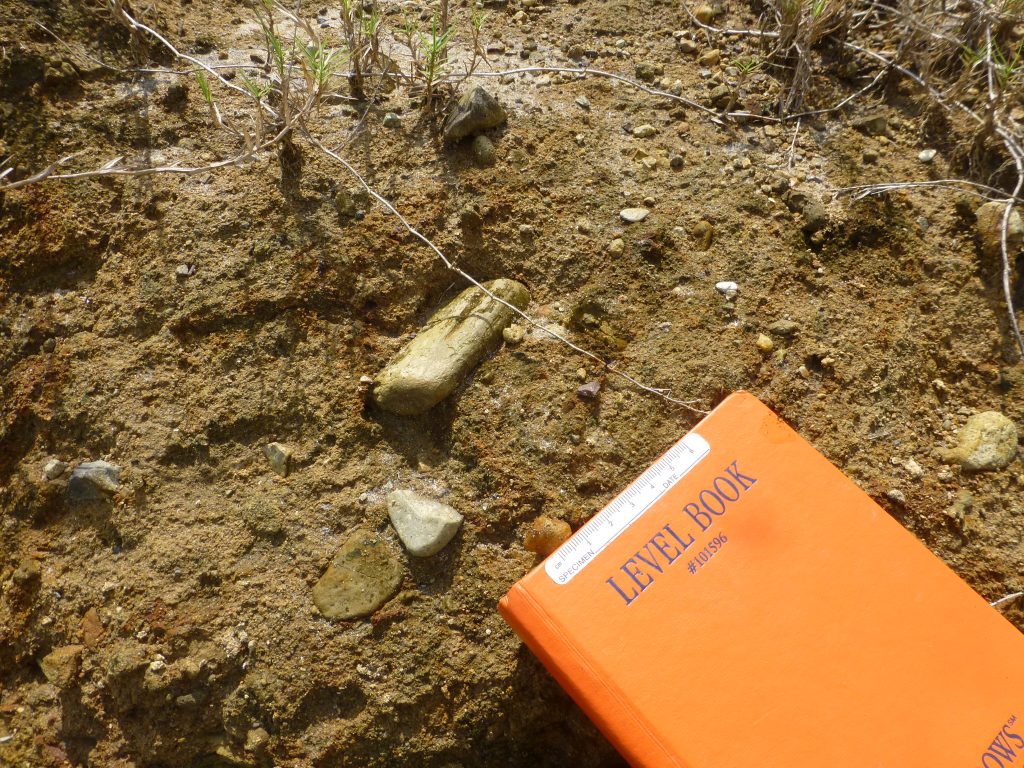

I started the day with Chris, Carolyn, and Jeremy by collecting fossil wood for a project that Jeremy is working on. The rest of our group (nine more) walked north along the shore of the lake to a site where a fossil echinoid was collected a few months back. After about three hours we caught up with the invertebrate crew in a nice open area where we could have lunch and prospect a limestone outcrop.

Just as I sat down for a water break, post doc Adiel Klompmaker hollered out to me from a little farther down the shore “Nathan, you’re going to want to take a look at these!” I knew he must have found some plant remains, so I hurried over. As I arrived, I could see undulating laminae of fine-grained material covering the limestone, and Adiel explained that the pattern was probably produced by algae. He handed me rock he had just pulled from the algal deposit and on it was a fossil leaf with exceptionally well preserved venation!

Adiel amassed a collection of more than a dozen leaves, and Chris and Carolyn identified the layer where Adiel found the first leaves and managed to collect more from nearby. In total, we collected ~50 leaves and leaf fragments before we started hearing thunder nearby and decided to pack up. The hike back to the cars was long and uphill through the forest.

I am excited to see these prepared back at the lab. Some of them seem to be three-dimensionally preserved, and perhaps the cellular structure of the mesophyll is intact! Perhaps we will find that the leaves belong to the same families as the fossil wood, and we might even find evidence of plant-animal interactions in the form of insect damage. I think we collected several different species, and I hope to make some preliminary estimates of paleoclimate using leaf physiognomy.