By Dipa Desai | PCP PIRE 2015-2016 Field Intern

During the past few months in Panama, I have gained plenty of valuable experience working in the field. Every morning we leave the city and head to the canal in search of fossils. It has become routine, waking up at 5:45, slathering on plenty of sunscreen and bug spray, and loading the truck with field supplies.

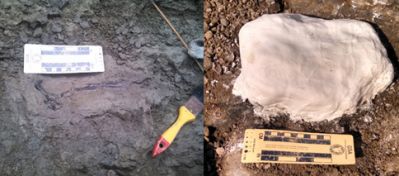

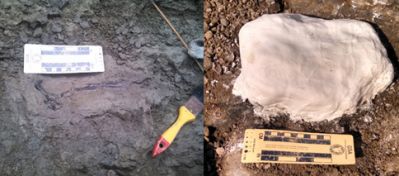

After navigating our way around the ever-growing potholes on the roads running along the canal, we reach our dig site for the day. The daily tropical rainstorms erode the outcrops and we prospect for the weathered fossils, also called float, lying on the surface. When we find a promising spot, we start to dig in hopes of uncovering intact fossils. My eye has gotten better at spotting fossils among the dark rock layers, and I have learned how to wrap and make plaster jackets for the larger fossils we find. Moreover, my knowledge of field geology and Panama’s geologic history has improved, and I am able to apply what I have learned to understanding its paleoenvironment.

However, being a field intern does not mean I spend all my time digging. In the afternoons when it inevitably rains, we take shelter in the lab and catalog all the fossils we collected that day. We also spend one day a week screen-washing the loose sediment we collect from fossiliferous layers to find the small fossils that we might otherwise miss in the field. Even recently, we took a departure from our normal schedule to scout out new cuts for potential fossil localities and take a look at the canal’s structural geology. The Canal Authority uses explosives, machinery, and dredging techniques to move tons of rock and expand the canal, and lucky for us, we have the opportunity to go through the fresh exposures for fossils.

It’s always exciting to find a fossil, but especially here in the Canal Zone. Panama is expanding their canal and the localities we go to are newly exposed cuts that will end up flooded after the expansion. Every fossil we unearth feels like we are discovering a little bit more about the paleoenvironment of the isthmus, which itself is a unique feature of Earth’s geologic history. The formation and closure of the isthmus had a profound effect on the region and Earth as a whole. It opened up a terrestrial route between South America and North America, allowing the interchange and radiation of faunas from both continents; it conversely closed the seaway between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, instigating vicariance among the populations separated by the newly formed landmass and, ultimately, altered the flow of ocean and wind currents around the world, affecting the Earth’s climate. The fossils we find here have the potential to tell us a great deal about how animals dealt with these environmental changes, and in turn how such changes shaped the course of their evolution. I am excited to continue field work and utilize my new skills to uncover more knowledge about Panama during the formation of the isthmus.

Por Dipa Desai | PCP-PIRE Becaria del campo

Traducido por Lucy Taylor

Durante los meses pasados en Panamá, he ganado mucha experiencia valiosa trabajando en el campo. Cada mañana salimos de la ciudad y vamos al canal a buscar fósiles. Ya es una rutina, despertándome a las 5:45, aplicándome el bloqueador solar y el repelente de insectos, y cargando el camión con suministros del campo.

Después de navegarnos alrededor de los baches en las calles al lado del canal, llegamos al sitio de excavación. Las tormentas tropicales diarias erosionan los afloramientos y buscamos los fósiles situados en la superficie. Cuando encontramos un sitio prometedor, empezamos a excavar con la esperanza que descubramos fósiles intactos. Mis ojos se han acostumbrado a notar los fósiles entre los niveles oscuros de la piedra, y he aprendido como envolver y hacer cubiertas de yeso para los fósiles grandes que encontramos. Además, mi conocimiento de la geología de campo y de la historia geológica de Panamá se ha mejorado, y ahora soy capaz de utilizar todo lo que he aprendido para entender el paleoambiente de Panamá.

Sin embargo, ser una becaria del campo no significa que paso todo el tiempo excavando. Por las tardes, cuando inevitablemente llueve, nos resguardamos en el laboratorio y catalogamos los fósiles que hemos recogido. También pasamos un día de cada semana tamizando el sedimento que recogemos del afloramiento para encontrar los fósiles pequeños que a veces podemos pasar por alto en el campo. Recientemente, hicimos una desviación de nuestro horario normal para buscar nuevos afloramientos y sitios de fósiles, y para investigar la geología estructural del canal. La Autoridad del Canal usa explosivos, máquinas, y técnicas de dragar para mover toneladas de piedras para ampliar el canal. Lo afortunado es que tenemos la oportunidad de examinar los nuevos sitios expuestos a buscar fósiles.

Siempre es emocionante encontrar un fósil, pero es algo especialmente aquí en la zona del canal. Panamá está ampliando el canal, y los sitios que visitamos son nuevos sitios que van a estar inundados de agua después de la expansión del canal. Con cada fósil que descubrimos, nos sentimos que aprendemos un poquito más hacia el paleoambiente del istmo, que es una característica única de la historia geológica de nuestro planeta. La formación y el cerramiento del istmo tuvo un efecto profundo en la región y en la tierra entera. Abrió una ruta terrestre entre Sudamérica y América del Norte, que permitía que el movimiento y la dispersión de especies de ambos continentes; por otro lado, cerró la ruta marina entre el mar caribeño y el océano pacífico. La nueva masa de tierra instigó la separación de las poblaciones de animales que separó, y alteró la corriente del océano y del viento de todo el mundo, afectando el clima mundial. Los fósiles que encontramos aquí tienen la potencial de darnos una vista de cómo los animales prehistóricos se enfrentaban a los cambios de su ambiente, y siguiendo eso, cómo los cambios dichos formó el camino de la evolución de esos animales. Estoy emocionada de continuar con el trabajo de campo, y de utilizar mis nuevas habilidades para descubrir más conocimientos de Panamá durante la formación del istmo.