The Fort and the Settlement

Contemporary accounts about the fort itself are ambiguous. Pedro Menéndez wrote that he sent his Captains ashore first to make an entrenchment, to protect goods and people that were being unloaded from the ships. They would subsequently, once the immediate threats and uncertainties of arrival were past, more carefully select a site for the fort. Father Mendoza wrote that they took a house of a chief, and made a fortification around it.

We do know that the first fort contained a storehouse, or casa de municiones, as well as the lodgings of the expedition’s officials. Inside the casa de municiones the Spaniards stored corn, meat, cassava, wine, oil, garbanzos, other foodstuffs, cloth, sails, and munitions. Eyewitnesses recount that although the building had a stout wooden door, it was constructed of palm thatch. The Spaniards referred to the building as a buhio, the word used in the Caribbean to describe a thatched hut, and sometimes a large house of a cacique.

It would have been traditional to build a moat and an earthwork around the fort; however many of the early Spanish forts in Florida did not have moats. At Menendez’s other townsite of Santa Elena, which he established in 1566, their Fort San Felipe did not have a moat until four years after the fort itself was constructed*. And no trace of the first Santa Elena fort of 1566, San Sebastian, has ever been found.

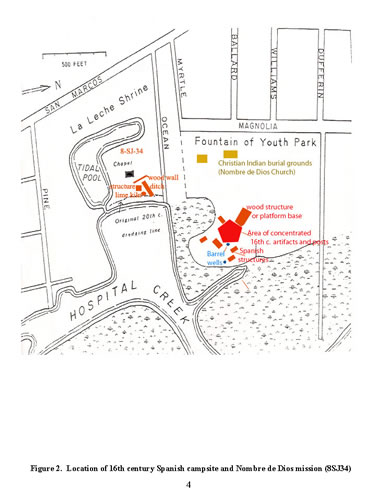

Archaeological excavations have uncovered features dating to the Menéndez period at both the Fountain of Youth Park site (8-SJ-31) and the Nuestra Señora de la Leche site(8-SJ-34), also known as the Nombre de Dios Site.

*(Stanley South, 1983, Revealing Santa Elena 1982. Research Manuscript Series 188. The University of South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology. Columbia. P. 43.

The La Leche Shrine Features (8-SJ-34)

The Moat/Entrenchment Ditch

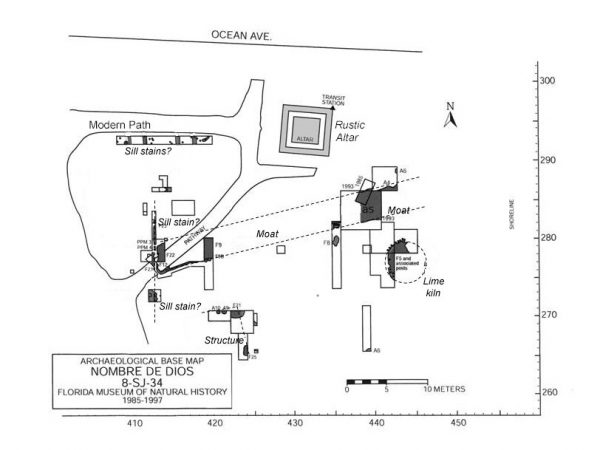

The clearest evidence for European-style fortification comes from the Nuestra Señora de la Leche Shrine site (8-SJ-34), located directly to the south of the Fountain of Youth Park. Excavations at this site located a moat or entrenchment ditch, possible log sleeper stains (wall sill supports placed directly on the ground) and very large posts from a square or rectangular structure.

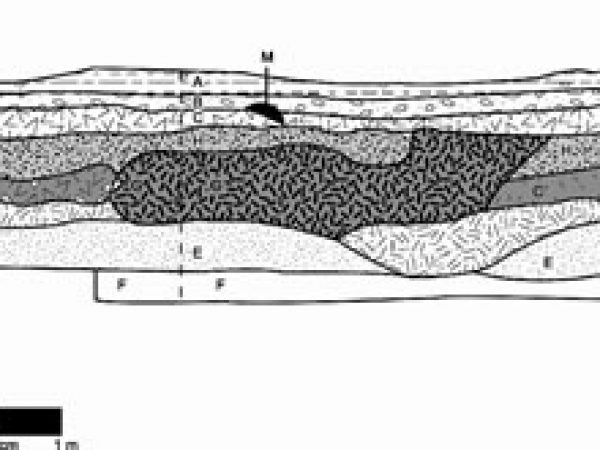

The “ditch” was a straight, linear trench that extended inland (westward) from the waters edge for 30 meters, and then ended abruptly without turning. The eastern (waterside) end of the ditch has been destroyed by modern erosion and shore stabilization activities. A narrow linear stain, perpendicular to the end of the ditch itself, marked the western (inland) end of the ditch. This stain appears to be from a sleeper sill for a wooden wall. After abandonment, the moat was filled in with dirt that included Native American and Spanish pottery, a sherd of Ming porcelain, and a fragment of a kaolin pipe (which is thought, because it is the only post-sixteenth century artifact in the fill, to have been introduced by root and gardening activity).

On the north side of the ditch, additional narrow sleeper stains were found, and to the south there were three large postholes that supported a small but sturdy building. The posts from the building seem to have been placed during the 16th century, but removed and backfilled in the seventeenth century.

All of these features are consistent with what might be expected at a military site, however, there is no evidence of either a Timucua structure or pre-contact occupation at this site. Neither is there extensive evidence for Spanish domestic occupation. This may be the location of the initial “entrenchmnent” dug by the Spanish soldiers prior to the landing and unloading of the ships, or it may alternatively represent the “casa fuerte de San Agustín el Viejo”, left in 1566 when the first settlement was abandoned.

We also cannot definitively reject the possibility that these features are associated with one of the later sixteenth century forts at St. Augustine, however the absence of other defensive or structural features, and the peculiar nature of the “moat” make this less likely.

The lime kiln

A sixteenth century lime-burning pit, or pot kiln, was also found to the south of the moat at the La Leche shrine site. This was a roughly circular pit, some 4 meters in diameter, and 1.5 meters deep. It was lined with burned pine logs, and had a flat base of charcoal. The sand under the logs and wood floor was burned to a bright red color. Layers of reduced oyster shell lime were found in the kiln, and the final load of oyster shell – as yet unburned – remained in the kiln when it was abandoned.

Two radiocarbon dates were generated from the burned logs that lined the lime-burning pit, suggesting that the logs that lined the kiln were cut in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, and probably used to construct the kiln after the Spaniards arrived in the mid- 16th century. The dates, at 2 sigmas, were Cal AD 1445-1645 (intercept 14985, Beta 80775) and Cal AD 1305-1460 (intercept AD 1420, Beta 80776). However, the presence of a white opaque, tumbled cane glass bead with spiral blue stripes, and a piece of Ming porcelain in the fill indicate that the kiln was abandoned and filled during the sixteenth century.