Florida scientists have tagged a deep-sea shark from a submersible, a historic first that took three expeditions, more than 2,000 pounds of bait, custom-built spear guns and over a dozen tries.

After multiple attempts were scuppered by bad weather, misfiring spear guns, an interloping grouper and an absence of sharks, an OceanX team led by Florida State University ecologist Dean Grubbs and Cape Eleuthera Institute researchers Brendan Talwar and Edd Brooks made one final dive on the night of June 29.

In the hot seat of OceanX’s submersible Nadir was Gavin Naylor, one of Grubbs’ collaborators and director of the Florida Program for Shark Research at the Florida Museum of Natural History. The submersible was armed with two satellite tags – Naylor would have just two chances to pin one to a bluntnose sixgill, a species of shark that Grubbs has been researching for nearly 15 years.

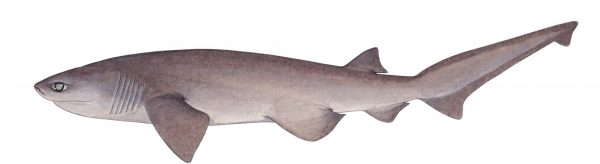

Illustration by Lindsay Gutteridge

Grubbs had one piece of advice for Naylor before Nadir descended off the coast of Eleuthera in the Bahamas, where the ocean floor plummets to a depth of more than a mile: “Don’t hesitate,” he said. “Take the shot.”

Naylor saw his opportunity when a male sixgill approached the sub at more than 1,700 feet below sea level. He fired. The team later used video footage to confirm the tag was implanted in the shark’s side.

Naylor, who had never previously been in a sub and considers himself more of a genetics nerd than a Rambo of the sea, said his successful shot was “dumb luck.”

Grubbs’ response: “We’ll take it either way.”

The tag will record data on the shark’s depth and ambient light and temperature every few minutes for three months, giving researchers a portal into the habits and movements of bluntnose sixgills, Hexanchus griseus. After three months, the tag will dislodge, float to the surface and transmit the stored data to a satellite link.

Bluntnose sixgills are large, poorly understood sharks that primarily inhabit depths between 650 and 3,300 feet, a region of the ocean known as “the Twilight Zone,” though Grubbs has also recorded them swimming to 5,000 feet deep. They belong to a lineage that dates back more than 180 million years, predating the origin of many dinosaurs.

“It was like seeing a T. rex in the water,” Naylor said. “This lineage has been around for 100 times as long as Homo erectus (the ancient ancestor of humans), and these sharks haven’t changed that much.”

With large green eyes and coxcomb-shaped teeth that function like a chainsaw, bluntnose sixgills can grow up to 20 feet long. But despite their charisma, they “have had almost zero attention in terms of research,” Grubbs said. “When I said I wanted to study them, other scientists said there was no way to do so. I took that as a challenge to prove them wrong.”

Grubbs has satellite-tagged more than 20 bluntnose sixgill sharks since 2005. But for the past decade, he has been searching for a way to tag the sharks in their deep-sea habitat rather than bringing them to the ocean surface, which can increase their stress and recovery time. He and Talwar spent months working with OceanX and spear gun manufacturers to design a system that could tag the sharks at their native depths.

“So much money has been expended on tagging great whites, and here we have a comparably sized predator, and we know almost nothing about it,” Grubbs said. “Are they really rare? The answer may be that not many people are looking for them.”

Naylor described the deep-sea dive as “probably the most magical experience I’ve ever had.”

“We were in pitch darkness in this globe. I was completely transfixed by being underwater in this other world,” he said. “The hair on the back of my arms was standing up.”

Florida Museum photo by Gavin Naylor

As Nadir piloted deeper, Naylor saw bristle worms, sea cucumbers, lobster larvae and a “conga line of Cuban dogfish.” Then, as the sub coasted to rest on a shelf, “an enormous beast came up” – the first sixgill shark. It was followed by a large 16-foot-long female that made a careful examination of the entire sub, nosing the glass to peer inside.

“She was studying us,” Naylor said. “It was delightful for me to see a shark being curious. We’d be arrogant to think we were the only ones doing the evaluating.”

The satellite tags were provided by collaborators Lucy Howey and Lance Jordan. Lee Frey piloted Nadir, a Triton 3300/3 submarine that was launched from the Alucia, an OceanX research vessel. The Cape Eleuthera Institute coordinated the expeditions. The mission was made possible by a partnership between OceanX, Bloomberg Philanthropies’ Vibrant Oceans Initiative, the Moore Bahamas Foundation and the Wildlife Conservation Society to create “One Big Wave” of ocean exploration and protection globally.

Sources: Gavin Naylor, gnaylor@flmnh.ufl.edu, 352-273-1954

Dean Grubbs, dgrubbs2@fsu.edu

- Watch OceanX’s video of the dive on Facebook.

- Learn more about bluntnose sixgill sharks.