Palmetto Fauna

University of Florida Vertebrate Fossil Locality PO005, along with over 85 individual mines or specific areas within mines. A list of mines and their locality numbers provided below.

Location

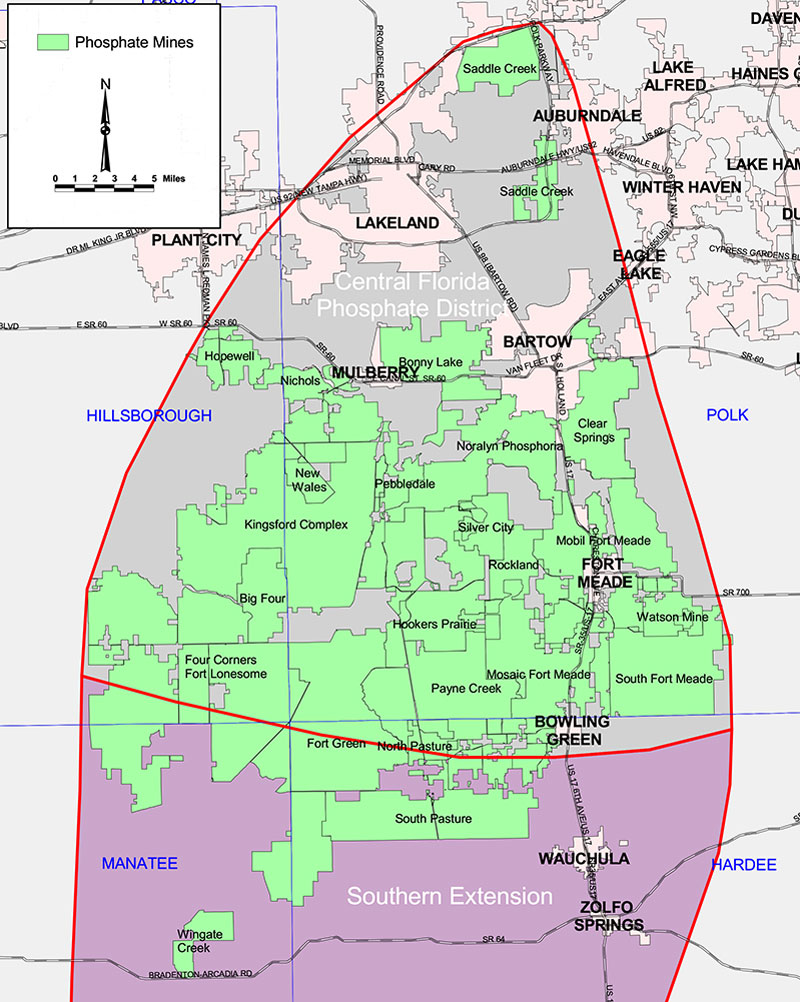

The Palmetto Fauna derives from the Central Florida Phosphate District, a region of commercial open-pit mines that includes southwestern Polk County, northwestern Hardee County, southeastern Hillsborough County and northeastern Manatee County (see Figure 1).

Age

- Early Pliocene Epoch; latest Hemphillian (Hemphillian 4) land mammal age

- 5 to 4.5 million years ago

Basis of Age

Vertebrate Biochronology. The terrestrial component of the Palmetto Fauna shows greatest similarity to Hemphillian 4 faunas from the western and central United States (e.g., Mount Eden [California]; Santee [Nebraska]; Buis Ranch [Oklahoma]) and Mexico (Yepómera and El Ocoté). Among the key species linking the Palmetto Fauna to one or more these are: Rhynchotherium edense, Hemiauchenia edensis, Catagonus brachydontus, Dinohippus mexicanus, and Pseudhipparion simpsoni. The marine component of the Palmetto Fauna likewise compares very well with that produced by the early Pliocene Yorktown Formation in the Lee Creek Mine, North Carolina.

Geology

The fossils of the animals making up the Palmetto Fauna are derived from the Bone Valley Formation (sometimes considered the Bone Valley Member of the Peace River Formation-see Scott, 1988). The major minerals forming the Bone Valley Formation are siliclastic minerals, especially quartz and clays such as smectitite and palygorskite, the phosphatic mineral francolite, and the magnesium carbonate mineral dolomite (Scott, 1988; Compton, 1997). Individual beds vary greatly in their grain size, presence/absence of bedding, lateral extent, thickness, and mineralogical composition.

The Bone Valley Formation overlies the Arcadia Formation, which is an indurated unit of limestone and dolostone (Scott, 1988). Their contact is an erosional unconformity, sometimes with evidence of ancient sinkhole formation into the Arcadia. A zone of coarse phophatic rubble or clays generally separates the two. In the Central Florida Phosphate District the thickness of the Bone Valley Formation can exceed 50 feet (15 m), but is normally between 25 and 50 feet. The Bone Valley Formation is covered by unconsolidated Pleistocene sands.

Depositional Environment

Nearshore marine environments, including low energy bays (clay-rich beds) and high energy channels (gravel beds).

Fossils

The Bone Valley Formation is one of the richest producers of vertebrate fossils in the state, such that large numbers of specimens exist in museum and private collections. The Florida Museum of Natural History collection contains about 50,000 catalog numbers assigned to Palmetto Fauna specimens; of these about 27,000 are cartilaginous fishes (sharks and rays), 5,000 bony fishes, 6,000 reptiles, 2,700 birds, and 9,300 mammals. Other museums with substantial collections are Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology and the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, while lesser numbers are found elsewhere. Despite these high numbers, it must be assumed that most specimens in the region are either never found and then re-buried as mined areas are reclaimed, or are physically destroyed by mining processes and treatment plants. The abundant fossils in the Central Florida Phosphate District gave the area its nickname, the Bone Valley. Fossils of taxa belonging to the Palmetto Fauna can be found throughout the entire Central Florida Phosphate District but were especially common in the mines located in the area bounded by the towns of Bradly Junction, Fort Meade, Bowling Green, and Fort Green. Unfortunately there are no longer any active mines in this area.

The most common fossils in the Palmetto Fauna are isolated teeth of sharks and myliobatoid rays. These vary in condition from pristine to highly waterworn. As fossil teeth of many of the same shark and ray species occur in older faunas of the Central Florida Phosphate District, some of those found in Palmetto Fauna assemblages may be reworked from older beds. Also very common are the tail spines and dermal “thorns” of rays, the fused jaws plus teeth of diodontid porcupine fish, and individual bones from both marine and freshwater turtles. Bones of birds, especially from taxa common in coastal regions such as cormorants and auks are relatively abundant. Among terrestrial mammals, isolated teeth of horses are the most commonly found fossils.

There are currently 191 taxa recognized as members of the Palmetto Fauna, 20 sharks, 7 rays and sawfish, 39 bony fish, 3 amphibians, 21 reptiles, 38 birds, and 63 mammals (click the list below to see a detailed listing of all taxa). In general, the mammals are the best studied component of the fauna, followed by the birds, and then the turtles. Other taxa are poorly studied, especially the sharks, rays, and bony fish.

There is a strong taphonomic bias against small terrestrial fossils in the Bone Valley Formation. Most of the fossils found are bones and teeth from animals that weighed more than 20 pounds (10 kg.). This means that fossils of frogs, salamanders, lizards, snakes, and small mammals such as moles, shrews, rodents, and rabbits are very uncommon.

Excavation History and Methods

There are no known natural geologic exposures of the Bone Valley Formation, so all Palmetto Fauna fossils have been found as a by-product of phosphate mining. During the first half of the 20th century, there is little in the way of actual fossil collecting by professional paleontologists. Most specimens were found by mining geologists or workers and accumulated in mine offices. Paleontologists visiting Florida acquired Palmetto Fauna specimens by visiting the offices and asking for donations. By this method, specimens made their way to museums in Washington, New York, Ann Arbor, and Cambridge. This means that there was little in the way of firsthand information on the geology, stratigraphy, and field relationships of the specimens.

S. David Webb arrived as a new curator at the Florida State Museum in 1964, bringing with him a western style of vertebrate paleontology that emphasized the stratigraphic relationships of fossil-bearing deposits. Based on his field notebooks archived at the museum, Webb made repeated collecting trips to the Central Phosphate Mining District in the 1960s and early 1970s, forging relationships with mining geologists which allowed him and his students open access to the mines and with amateur collectors who showed him their collections, provided advise based on years of experience, and made donations of key specimens. One of Webb’s graduate students, John Waldrop, already had vast experience collecting fossils in Florida and became extremely proficient at finding specimens in the phosphate mines and in working out the stratigraphic relationships of the deposits. After completing his master’s degree, Waldrop settled in nearby Lake Wales where he taught school and brought his students out fossil collecting in the mines. He built up a large, well organized collection whose specimens were made available for use by researchers. All of Waldrop’s fossils were donated to the Florida Museum of Natural History.

Webb and Waldrop concentrated their collecting efforts beyond simply collecting the spoil piles made by mining operations, but in working on the face of the new exposures of sediment created by the draglines. These could only be worked for a short time until the dragline returned, mining away that exposure and creating a new one. Over time, Webb, Waldrop, and others such as mining geologist Donald Crissenger built up collections of specimens that were found together in the same geologic deposit. They discovered that there were four major assemblages of co-occurring fossil vertebrates found in the Central Phosphate Mining District. In some places two assemblages were found in one outcrop made by a dragline, so that they could use the basic stratigraphic principles of superposition and cross-cutting relationships to determine the relative ages of the assemblages. The Palmetto Fauna is the youngest of these vertebrate fossil assemblages found in the Bone Valley Formation.

The specimens were found by surface prospecting, walking up and down outcrops and spoil piles looking for exposed or partially exposed fossils. Once found most specimens could be collected directly, although a few required making plaster jackets. These prospecting efforts resulted in the discovery of two of the three known large Palmetto Fauna quarry finds. Waldrop discovered the Palmetto Mine Microsite in 1969, and both he and the Florida State Museum excavated there for the next two years. As the name implies, this was one of the few areas in which screenwashing was successful in recovering small vertebrate fossils. Although most of these are from marine fish and teeth of the stingray Dasyatis, some fossils of small freshwater species, such as the salamanders Amphiuma and Ambystoma, were found along with a few small rodent teeth. Waldrop and his colleague John Beaudua found the second such site, the TRO Quarry in the Payne Creek Mine in 1977. It was not as rich in small fossils but had greater diversity and numbers of terrestrial vertebrates. The third and last known large quarry site for the Palmetto Fauna was found in 1989 in the Fort Meade Mine. Known as the Whidden Creek Site, it too produced a mixed marine-terrestrial assemblage of several thousand specimens. It was primarily excavated in January 1990 by a crew of Florida Museum of Natural History staff/students and Tampa Bay Fossil Club volunteers.

At the present time, collecting in the Central Florida Phosphate District is extremely confined compared to before 2000. Mine managers restrict access to groups such as fossil clubs or university classes and collecting is only on spoil piles under their supervision. Strictly enforced safety regulations prohibit collecting in cuts or areas with active machinery.

Discussion

The first descriptions of fossils from the Central Florida Phosphate District were by state geologist E. H. Sellards (1910, 1915a; 1915b; 1916a; 1916b). From then until the 1950s, all of the fossils from the Bone Valley Formation were considered the same age. The term ‘Bone Valley Fauna’ was in wide use during this interval. Initially this age was thought to be similar to that of Mixson’s Bone Bed, and some fossils were mistakenly referred to species named from that site (Simpson, 1930). Later, a split developed between those that did research on the marine dugongs and cetaceans from the Bone Valley Formation (e.g., Allen, 1941; Kellogg, 1944) and those that studied land mammals such as horses and carnivores (e.g., Simpson, 1933; Stirton, 1936; Wood et al., 1941). Those working on marine mammals thought that the Bone Valley Fauna was Miocene, while those working a land mammals thought it was Pliocene. The cause of this discrepancy was because of the assumption that all of the fossils were the same age. It turns out that while most of the land mammals known at this time are from the Palmetto Fauna, most of the marine mammals are from the older Agricola Fauna. Later, once multiple age faunas were established for the Bone Valley Formation, the term ‘Upper Bone Valley Fauna’ was frequently used (e.g., MacFadden and Galiano, 1981; Berta and Morgan, 1985; MacFadden, 1986) for what Webb and Hulbert (1986) designated as the Palmetto Fauna. Webb et al. (2008) reviewed the land mammals of the Palmetto Fauna and discussed the criteria by which species are assigned to a fauna in the Bone Valley Formation. The Palmetto Fauna correlates with the fourth (and youngest) subinterval of the Hemphillian land mammal age. The Hemphillian 4 contains the Miocene-Pliocene boundary, so it correlates with the latest Miocene and earliest Pliocene of the standard geologic time scale (Tedford et al., 2004). The Palmetto Fauna is generally thought to be one of the youngest of the Hemphillian 4 faunas, as it contains some species which elsewhere are only known from the succeeding Blancan land mammal age, such as Lynx rexroadensis.

Forty-two new species have been proposed on the basis of specimen from the Palmetto Fauna: 3 reptiles (all turtles), 12 birds, and 27 mammals (Table 1). Some of these have been synonymized with each other, or older species names, from localities other than the Palmetto Fauna.

Table 1. New species named on the basis of a specimen from the Palmetto Fauna. The left column has the original species name as indicated in the original paper; the middle column the author(s) and year of publication; and the right column the current valid species name.

| Original Species Name | Author and Date | Current Species Name |

| Testudo hayi | Sellards 1916 | Hesperotestudo hayi |

| Hipparion minus | Sellards 1916 | Nannippus aztecus |

| Agriotherium schneideri | Sellards 1916 | Agriotherium schneideri |

| Serridentinus simplicidens | Osborn 1923 | Gomphotherium simplicidens |

| Serridentinus brewsterensis | Osborn 1926 | Rhynchotherium edense |

| Serridentinus bifoliatus | Osborn 1929 | Rhynchotherium edense |

| Kogiopsis floridana | Kellogg 1929 | Kogiopsis floridana |

| Testudo louisekressmanni | Wark 1929 | Hesperotestudo hayi |

| Hipparion phosphorum | Simpson 1930 | Neohipparion eurystyle |

| Pliomastodon sellardsi | Simpson 1930 | Mammut matthewi |

| Gavia concinna | Wetmore 1940 | Gavia concinna |

| Goniodelphis hudsoni | G. M. Allen 1941 | Goniodelphis hudsoni |

| Hexameryx simpsoni | White 1941 | Hexameryx simpsoni |

| Pliogulo dudleyi | White 1941 | Borophagus dudleyi |

| Prosthennops elmorei | White 1942 | Mylohyus elmorei |

| Hexameryx elmorei | White 1942 | Hexameryx simpsoni |

| Balaenoptera floridana | Kellogg 1944 | Balaenoptera cortesii |

| Pliodytes lanquisti | Brodkorb 1953 | Pliodytes lanquisti |

| Phoenicopterus floridanus | Brodkorb 1953 | Phoenicopterus floridanus |

| Larus elmorei | Brodkorb 1953 | Larus elmorei |

| Ardea polkensis | Brodkorb 1955 | Ardea polkensis |

| Bucephala ossivallis | Brodkorb 1955 | Bucephala ossivallis |

| Phalacrocorax wetmorei | Brodkorb 1955 | Phalacrocorax wetmorei |

| Morus peninsularis | Brodkorb 1955 | Morus peninsularis |

| Sula guano | Brodkorb 1955 | Sula guano |

| Sula phosphata | Brodkorb 1955 | Sula phosphata |

| Alca grandis | Brodkorb 1955 | Alca grandis |

| Erolia penepusilla | Brodkorb 1955 | Erolia penepusilla |

| Osteoborus crassapineatus | Olsen 1956 | Borophagus hilli |

| Rhynchotherium simpsoni | Olsen 1957 | Rhynchotherium edense |

| Tapiravus polkensis | Olsen 1960 | Tapirus polkensis |

| Chrysemys inflata | Weaver and Robertson 1967 | Trachemys inflata |

| Carpocyon limosus | Webb 1969 | Carpocyon limosus |

| Antilocapra garciae | Webb 1973 | Subantilocapra garciae |

| Kyptoceras amatorum | Webb 1981 | Kyptoceras amatorum |

| Arctonasua eurybates | Baskin 1982 | Arctonasua eurybates |

| Enhydritherium terraenovae | Berta and Morgan 1985 | Enhydritherium terraenovae |

| Pseudhipparion simpsoni | Webb and Hulbert 1986 | Pseudhipparion simpsoni |

| Eocoileus gentryorum | Webb 2000 | Eocoileus gentryorum |

| Nanosiren garciae | Domning and Aguilera 2008 | Nanosiren garciae |

| Rhizosmilodon fiteae | Wallace and Hulbert 2013 | Rhizosmilodon fiteae |

| Sternotherus bonevalleyensis | Bourque and Schubert 2015 | Sternotherus bonevalleyensis |

While there are many Hemphillian sites and faunas in Florida, all of them but the Palmetto Fauna belong in either the Hemphillian 1 or Hemphillian 2 intervals. There are no known Hemphillian 3 faunas in Florida. Thus there is a gap in the fossil record of the state between about 6.5 million years ago, the age of sites such as Withlacoochee River 4A and Manatee County Dam, and about 4.5 million years ago. While some mammal species persist from the Hemphillian 2 to the Hemphillian 4, most do not, so there is a high degree of turnover among mammal species during this interval. There is a similar gap in the fossil record of Florida following the Palmetto Fauna, at least among land vertebrates, from about 4.5 million years ago to about 2.5 million years ago. And again there are very few mammal species that persisted from the Hemphillian 4 to the late Blancan. The Palmetto Fauna remains the largest and best known late Hemphillian assemblage in the eastern United States for land vertebrates. Two others have been found relatively recently in Tennessee and Indiana, the Grey Fossil Site and the Pipe Creek Sinkhole Site, respectively (Farlow et al., 2001; Hulbert et al., 2009).

When compared to Hemphillian 4 fossil faunas from Mexico and the western United States, the land mammals of the Palmetto Fauna show some significant differences (Webb et al., 1995). The diversity and abundance of brachydont, browsing ungulates is greater in the Palmetto Fauna, including the deer Eocoileus and the deer-like Floridameryx, two species of tapir, Gomphotherium simplicidens, and two peccaries. There is also a greater species number of horses, and among these, the three-toed hipparions far outnumber one-toed species (Webb et al., 2008). The family Protoceratidae persisted in Florida, in the form of Kyptoceras, far longer than it did in the west. Altogether this suggests a wetter climate in Florida, with more trees and shrubs, and fewer areas of pure grasslands.

Careful excavation of in situ deposits such as the Palmetto Mine Microsite and the Whidden Creek Site demonstrate that marine and freshwater/terrestrial fossils are truly found together in the same deposits and not mixed up by mining activities. How can the remains of such ecologically different animals be found in the same deposit in such large numbers? One possible scenario is that carcasses and bones of land and freshwater-inhabiting species are transported by rivers to nearshore marine environments such as a bay, where they become buried in sediment along with the remains of marine species living in the region. A second mechanism requires a change in sea level: land close to the shoreline becomes inundated by rising sea level or a nearshore environment becomes dry land as sea level falls. Erosion and other geologic processes mix the sediments, causing the bones from the first and second environments to end up together, a process geologists call time-averaging. Although Florida Museum paleontologists traditionally favored the first scenario, comparison of the relative amounts of rare earth elements (REEs) in fossils of terrestrial and marine species from the Palmetto Fauna revealed small but subtle differences (Hulbert and MacFadden, 2009). This means that they both could not have been buried together as “fresh” bones in the same sedimentary deposit. During at least some of the time it took to fossilize the bones (the time when REEs are taken into the bones), those from the marine species were in a different environment than those from terrestrial species.

The composition of the fishes in Palmetto Fauna and their relative abundances provide important information on the depositional environment. They can also be compared to the well-studied fossil fish assemblage from the Yorktown Formation at the Lee Creek Mine in North Carolina (Purdy et al., 2001). The Yorktown Formation produced 37 species of sharks and rays and 40 species of bony fish, mostly warm and cool water species. Purdy et al. (2001) concluded that the Yorktown Formation fish fauna represented an inner-shelf environment with few warm water species. The Palmetto Fauna has 27 taxa of sharks and rays and 39 taxa of bony fish. They collectively indicate an inshore, subtropical to tropical depositional environment. The relative abundances of Negaprion brevirostris (lemon shark), Pristis sp. (sawfish), Rhizoprionodon terranovae (sharpnose shark), Centropomus sp. (snook), Megalops sp. (tarpon), Sciaenops cf. S. ocellatus (red drum) are greater in the Palmetto Fauna than in the Yorktown Formation. These species prefer subtropical to tropical waters and are found predominately in relatively shallow to in-shore habitats. Species that are common or abundant in the Yorktown Formation, such as Acipenser sp. (sturgeon), Thunnus sp. (tuna), Epinephelus nigritus (black grouper), Pomatomus saltatrix (bluefish), and Notorynchus cepedianus (broadnose shark), are found primarily in cooler and/or deeper waters. These species are rare or uncommon in the Palmetto Fauna.

Table 2. Mines producing Palmetto Fauna fossils in the Central Florida Phosphate District. Fossil site codes beginning with PO are from Polk County, HI from Hillsborough County, HR from Hardee County, and MA from Manatee County. The given latitude and longitude are from the approximate center of the mine, some of which are quite extensive.

Sources

- Original Author: Richard C. Hulbert Jr.

- Original Completion Date: March 17, 2015

- Editor(s) Name(s): Richard C. Hulbert, Natali Valdes

- Last Updated: March 23, 2015

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Number CSBR 1203222, Jonathan Bloch, Principal Investigator. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Copyright © Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida